Politics turned Parody from within a Conservative Bastion inside the People's Republic of Maryland

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

Big Pharma Gets Diamond & Silk Canned

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

Sweden Achieves Herd Immunity

Thursday, April 23, 2020

Sunday, April 19, 2020

November No Shows?

Mary Shippee voted for Senator Bernie Sanders in Wisconsin’s Democratic primary this month, well after it was clear he had no chance to become the party’s presidential nominee.

Now that Mr. Sanders has dropped out and endorsed former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., Ms. Shippee is torn over whether to once again cast a vote for a moderate Democrat in November, after grudgingly supporting Hillary Clinton in 2016 and President Barack Obama in 2012.

“What it feels like is the Democratic Party relies on guilting progressives into voting for them, and they don’t want to have any meaningful changes,” said Ms. Shippee, 31, a nursing student in Milwaukee. “For the third election in a row, to have a candidate you’re not excited about makes me a little more interested in voting third party.”

Despite Mr. Sanders’s call to unite behind Mr. Biden to defeat President Trump — whom the Vermont senator described as “the most dangerous president” of modern times — and despite Mr. Obama’s assurance that the party had moved left since he left office, the youthful and impassioned army of Sanders supporters is far from ready to embrace a nominee so unlike the one they pinned their dreams on.

In interviews with two dozen Sanders primary voters across the country this week, there was a nearly universal lack of enthusiasm for Mr. Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee. Some called him a less formidable candidate than Hillary Clinton was in 2016. Many were skeptical of his ability to beat Mr. Trump. Others were quick to critique Mr. Biden’s sometimes incoherent speech.

Taken together, the voters’ doubts raised questions about how many would show up for Mr. Biden in November, including their likelihood to volunteer and organize for him, an important measure of enthusiasm. In a poll last month, four out of five Sanders supporters said they would vote for Mr. Biden, with 15 percent saying they would cross over to Mr. Trump, about the same share that did so in 2016.

Te’wuan Thorne, 24, said it was “up in the air” whether he would vote. A Sanders supporter who recently moved to New York City from Pennsylvania, where he is registered to vote, he said, “If I happen to be at my polling place, I would vote for Biden, but I’m not very enthusiastic about him whatsoever.”

Some Sanders primary voters said they would back a third-party candidate, a few said they would vote for Mr. Trump, and some were wavering about voting at all. Daniel Ray, 27, of Lancaster, Penn., planned to write in Tulsi Gabbard, the congresswoman from Hawaii who ended her long-shot bid for the Democratic nomination last month.

In Facebook groups for Sanders supporters and on Twitter, cynicism persisted about the olive branches on policy that Mr. Biden has offered to progressives and, at the extreme, some accused Mr. Sanders of selling out his leftist movement.

It is clear, if it wasn’t already, that the Sanders base is far different from the supporters of moderate candidates in the primaries, who moved on quickly from their first choices to coalesce around Mr. Biden early last month. For Mr. Sanders, bringing his people on board will not be easy, even though he endorsed Mr. Biden with seeming affection and months earlier than he did Mrs. Clinton in 2016.

Nathaniel Kesselring of Tucson voted for Mr. Sanders in the Arizona primary but said he would not vote for Mr. Biden because progressives should not compromise on issues like “Medicare for all” and free public college tuition.

“If we don’t declare as a movement that this isn’t good enough,” Mr. Kesselring said, referring to Mr. Biden’s moderate policies, “then the Democratic Party has every right to ignore us. I hate the idea of Donald Trump being president for another term, but if that’s what we need to do to make these people take us seriously, that’s what needs to be done.”

“I hate it,” repeated Mr. Kesselring, 45, the vice president of a buyer’s club for diabetes products. “I hate it. But I’m not moving.”

Certainly, as polling shows, the majority of Sanders voters plan to support Mr. Biden. Most of those interviewed who intend to do so called it a hold-your-nose election.

“I will vote for him; Biden is better than Trump, sure,” said Stephen Phillips, 33, who lives in Lakeland, Fla., and has been furloughed from his job in talent recruitment because of the coronavirus outbreak. But he cringed watching Mr. Sanders’s live-streamed endorsement of Mr. Biden on Monday, when the senator spoke extemporaneously while the former vice president seemed to be reading off cue cards. “This guy is going to be running against Donald Trump, who off the cuff can destroy anybody with words.”

Maria Aviles-Hernandez, 24, a Spanish teacher near Rocky Mount, N.C., didn’t vote in 2016 but plans to support Mr. Biden, although Mr. Sanders was her first choice. “I will vote this year, I will make sure of that,” she said. “I didn’t expect Trump to win the first time. The world just surprised me. I don’t want that to happen again.”

A challenge for Mr. Biden in the fall is that even if he has the grudging support of Sanders voters, many may not go out of their way to vote, either by applying for absentee ballots or by traveling home if they are students.

“For a college student, the barriers to get to the voting place are very real,” said Victoria Waring, 21, whose family home is in central Pennsylvania but who attends college in Philadelphia, studying film and animation. “A lot of my friends are disillusioned with the Democratic Party, they feel there’s nothing they can do to be represented, that the establishment will pick whoever they want and it doesn’t matter what we say.”

In 2016, before she was old enough to vote, Ms. Waring organized for Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate. Ms. Waring said she would not volunteer this year for the Biden campaign. “How could I in good faith tell someone to vote for someone who I don’t agree with on any issue?” she asked. “I can’t. No. Absolutely not.”

One survey after the 2016 election indicated that 12 percent of Mr. Sanders’s primary voters ended up voting for Mr. Trump in the general election. Another 8 percent of Sanders supporters voted for a third-party candidate, and 3 percent did not vote. The numbers were in line with past elections when a losing candidate’s primary voters did not support the nominee. But because the 2016 race was so close, with Mr. Trump winning by less than one percentage point in three crucial Rust Belt states, the Sanders drop-off voters helped tilt the election away from Mrs. Clinton.

Younger voters, who overwhelmingly backed Mr. Sanders in this year’s primary race, said Mr. Biden seemed like just another politician with wishy-washy positions on climate change and health care. What they craved, they said, was the type of fundamental change that Mr. Sanders has espoused for decades.

“Joe Biden, he seems fake to me,” said Jacob Davids, 21, a college student in Milwaukee. “I don’t know his policies, and if you haven’t put enough effort into P.R. and media to make viewers like me know where you stand, I’m not going to vote for you.”

Kevin Ridler, 55, voted for Mr. Sanders in this year’s Democratic primary and cast a ballot for Mr. Trump in the 2016 general election. Mr. Ridler lives in rural western Iowa and is the president of a railway maintenance workers’ local in the Midwest. He said he had believed Mr. Trump’s promises that he would be a friend of American workers. Immediately after the election, Mr. Ridler said, his union’s railroad employer refused to renegotiate a contract, citing a “new political climate,” and workers were forced to take a pay cut.

Mr. Ridler now calls his vote for Mr. Trump “a mistake” that he will not repeat.

He supported Mr. Sanders in Iowa’s caucuses. But he has a powerful dislike of Mr. Biden, whom he called dishonest, throwing in a few epithets. “I think he’s got dementia,” he said.

“Honestly, I hate to not vote at all,” he said, speaking from a railway bridge under construction outside Jefferson City, Mo. “I know that’s not the right thing to do, but that’s kind of what’s going to happen here.”

Robert Grullon, 29, a carpenter at a door factory near Melbourne, Fla., liked Mr. Sanders’s promises to raise the minimum wage and provide health care for all. “We love Bernie,” he said. “Bernie’s our guy.”

He complained that Hispanic voters and black voters — he is third-generation Dominican-American — tend to support Democrats but don’t get much back. “When are they going to have something for blacks and Hispanics, just for us?” he said. Mr. Biden struck him as just another politician in a blue suit.

“To tell you the truth, Trump might get my vote,” he said. “Donald Trump is a person who’s always been known in our community — I like hip-hop — we idolized him because he was a billionaire, he has been in rap videos, he has friends who are African-American.”

In eastern Iowa on Tuesday, Kelly Manning had just finished her route as a letter carrier for the Postal Service, which has lost millions in revenue during the pandemic even as Mr. Trump tries to block relief funding for the agency. Ms. Manning, 55, caucused for Mr. Sanders in Burlington, on the Mississippi River. She heard Mr. Biden speak when he came through Iowa, though she said he had made her nearly doze off.

“I’ll hold my nose and vote for Biden,” she said.

Her 31-year-old son, Mason Blow, is another matter. A staunch Sanders supporter, he voted for a third-party candidate in 2016. Ms. Manning said she and her sister were “working on him” to vote for Mr. Biden, to prevent a second Trump term.

“He said he won’t vote for Biden, he’s going to write in Bernie this time,” Ms. Manning said. “The younger people, they’re not used to having their dream crushed as we are."

Saturday, April 18, 2020

It's Just the Flu, People...

from SFGate

Large-scale Santa Clara antibody test suggests COVID-19 cases are underreported by factor of 50-85

It has long been assumed by medical experts that the United States is drastically underreporting the actual number of COVID-19 infections across the country due to limited testing and a high number of asymptomatic cases.

Large-scale antibody tests are expected to give researchers an idea of just how widespread the outbreak is, and preliminary results from the first such test in Santa Clara County suggest we are underreporting cases by at least a factor of 50.

In early April, Stanford University researchers conducted an antibody test of 3,300 residents in the county that were recruited through targeted Facebook ads. Researchers hoped to put together a sample that was representative of the county's population by selecting individuals based on their age, race, gender and zip code to extrapolate study results to the larger community.

The results of the study are preliminary and not peer-reviewed, but the general takeaways would seem to strongly contribute to the notion that there have been a large number of COVID-19 cases that went undetected.

Due to questions over the antibody tests' efficacy, researchers adjusted for test performance characteristics by using the test manufacturer's data and a sample of controls tested at Stanford University. Again, the results are preliminary and the study has not been peer-reviewed, but researchers found a raw, unadjusted antibody prevalence of 1.5 percent, which was scaled up to 2.5-4.2 percent when adjusting for population and test performance characteristics.

Researchers estimate that if 2.5 to 4.2 percent of the county has already been infected, the true number of total cases in early April — both active and recovered — ranges between 48,000 and 81,000. The county had reported just under 1,000 cases at the time the study was conducted, which would mean cases are being underreported by a factor of 50 to 85.

“Our findings suggest that there is somewhere between 50- and 80-fold more infections in our county than what’s known by the number of cases than are reported by our department of public health," Dr. Eran Bendavid, the Stanford professor who led the study, told ABC News.

If the study's numbers are accurate, the true mortality and hospitalization rates of COVID-19 are both substantially lower than current estimates, and due to lag between infection and death, researchers project a true mortality rate between .12 and .20. Results also suggest the county is nowhere near "herd immunity," as scientists estimate that 50-60% of the population would need to be infected for the virus to have nowhere to spread.

However, the study's authors caution against extrapolating Santa Clara County results to the rest of the country. The county reported its first case on January 31, and was one of the early national "hot spots" where the virus had gained a foothold. Researchers also acknowledge other limitations of the study, including an overrepresentation of white women between ages 19-64, and "other biases, such as bias favoring individuals in good health capable of attending our testing sites, or bias favoring those with prior COVID-like illnesses seeking antibody confirmation."

In San Mateo County, health officer Scott Morrow made a similar estimation on Monday night.

"I hesitate to give you the following numbers, because first of all they are a guess, and secondly because some will think they are too low to take action," he wrote in a message to the community. "My best guess is that approximately 2-3% of the SMC population are currently infected or have recovered from the infection. That’s around 15-25,000 people and they are all over the county and in every community. I don’t believe this number is off by a factor of 10, but it could be off by a factor of 2 to 3."

At the time of his announcement, the county had 699 confirmed cases of the virus, meaning if Morrow's numbers are correct, the county has identified just 2.7-4.5 percent of its total cases.

Friday, April 17, 2020

Have We Been Hoaxed?

from American Thinker

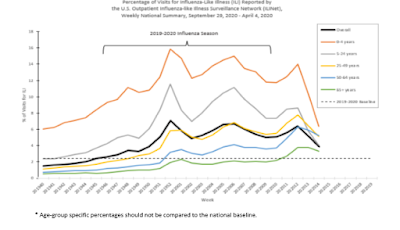

Is it not possible to assume that the Influenza-Like Illness (ILI) seen in American hospitals since January -- illnesses that weren't positive for flu but acted like the flu -- could have been untested SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and thus remained unknown? This has been recorded as one of the largest flu seasons in the U.S. since 2009 with hundreds of thousands of cases of ILI collected by CDC surveillance.

When CDC COVID-19 testing data are overlaid on a graph with reported influenza-like-illness data (because ILI numbers were at least two orders of magnitude higher, CDC COVID-19 testing numbers were multiplied by 100 to make a graphic comparison easier to see.), the data curves are strikingly similar. This could indicate that as people exhibiting flulike illnesses (110,554 in week 6) were seen by U.S. physicians unable to diagnose them with a known influenza, physicians with the ability, had ILI patients tested for COVID-19, sending those tests to the CDC for verification.

SARS Ig immunity appears (from non-peer reviewed research) to last for 12 years and continued comparison studies with SARS and SARS-CoV-2 indicates that CoV-2 response will mirror SARS.

So, though an increase in testing will inevitably capture more cases, if SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating in the population since November and has conferred immunity on surviving patients similar to SARS, the number of cases and COVID-19 deaths should stay relatively low -- and isn’t that what’s being reported in real time?

It’s important to analyze and remember this scenario as the U.S. emerges from its quarantine cocoon to the inevitable cries from politicians of “But we had to act to keep people safe,” and “If we hadn’t shut everything down the death rate would have been so much worse.”

It’s understandable when situations involving human life elicit emotional responses over the rational. Christian hearts especially are geared to Jesus’ new and most important of all commandments. But it appears that many more lives will be affected by hardships invoked through the current economic freefall than the virus itself. Now is the time to practice appropriate risk assessment for our nation and allow its citizens to get back to work. One day, a pandemic of real consequence will sweep across the globe. People will need to be able to listen to adept and accurate warnings without wondering if they’re hearing the Boy Who Cried Wolf.

Wednesday, April 15, 2020

Tuesday, April 14, 2020

Monday, April 13, 2020

Sunday, April 12, 2020

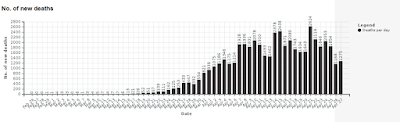

IS CDC Faking the Covid19 Death Data?

Source

So how come "Total" deaths are declining significantly in the last few weeks... while "Covid" deaths are up, deaths from "Influenza" and "Pneumonia" are down SIGNIFICANTLY? Is this simply a fake attribution of pneumonia and influenza (et al) related deaths to Covid?

The Swedes Have it Right

Sweden records just SEVENTEEN new deaths from coronavirus - its lowest daily rise in a fortnight - as new infections plummet to only 466 cases-Sweden has recorded 17 deaths and just 466 cases of the coronavirus on Friday

-The majority of cases came from Stockholm - where cafes and bars remain open

-The figures announced Friday are surprisingly low compared to previous days

-The country's total number of cases now stands at 10,151, with 887 known deaths

Sweden has seen its lowest increase in the coronavirus death toll for almost a fortnight, with only 17 fatalities reported on Friday.

The number of new cases also fell again to 466, following a two-day peak of 700+ cases per day.

The low figures come despite the country not enforcing a lockdown, piling pressure on the UK and other countries that did enact stricter measures to contain the virus.

The totals, announced at 2pm today, are surprisingly low compared to the sharp increase Sweden had been experiencing during the week.

The country's total number of cases now stands at 10,151, with 887 confirmed deaths.

However, trends in the data released by the country's Public Health Authority show that confirmed deaths and cases fall over the weekend before rising again, because of what is believed to be a delay in reporting.

The Stockholm and Sörmland regions have been hit hardest by the pandemic.

However today people were seen enjoying the sunshine outside cafes and bars in the Swedish capital on the eve of Easter Sunday, after officials did not enforce a shutdown.

Yesterday, the daily death toll and the number of new coronavirus cases both fell.

There 77 new deaths - down from 106 on Thursday. The number of confirmed infections went up by 544, a drop of nearly a quarter from yesterday's near-record figure of 722.

These figures will likely be used to pressure governments which have resorted to lockdowns to battle Covid-19 to lift the draconian restrictions.

More than 4,000 of the country's 9,685 confirmed cases are in the Stockholm area, according to official figures.

The government has also carried out random sampling which suggests that as many as 2.5 per cent of people in Stockholm have been infected.

That implies a higher figure of around 60,000 in the Stockholm region, suggesting that many people have had the virus without being added to the official count.

Unlike most of Europe, Sweden has not imposed a lockdown, and primary schools, shops, cafes, restaurants and bars remain open.

People are not generally ordered to stay at home, although they are told to isolate at the first sign of 'slight cold-like symptoms'.

Swedes are advised to 'keep your distance' at gyms and sports facilities rather than avoiding them altogether.

There is a ban on gatherings of more than 50 people, but the rule is far more generous than the limit of two that Britain and Germany have set.

Finland has already moved to limit border crossings, fearing that the virus will spread from Sweden.

The government in Stockholm has emphasised taking personal responsibility for public health, but most of its measures are not enforced.

The lack of a lockdown makes Sweden an outlier, but the government has rejected Donald Trump's claims that the country is 'suffering' more than others.

Asked at a White House briefing on Tuesday what advice he would offer to leaders who were skeptical of social distancing measures, Trump replied: 'There aren't too many of them... They talk about Sweden, but Sweden is suffering very gravely.'

Swedish foreign minister Ann Linde pushed back against Trump's claim that Sweden was not doing enough.

'We are doing about the same things that many other countries are doing, but in a different way,' Linde told broadcaster TV4.

'We trust that people take responsibility.'

Government epidemiologist Anders Tegnell said he did not believe Sweden was suffering any more than any other country.

'No, we don't share his opinion,' he told reporters, referring to Trump.

'Of course we're suffering. Everybody in the world is suffering right now, in different ways,' he said.

'But Swedish healthcare, which I guess he alludes to... is taking care of this in a very good manner.

'It's a lot of work, it's a lot of stress on the personnel and it's really a fight for them every day, but it's working.'

Prime minister Stefan Lofven says that while most measures were not bans he still expected all Swedes to comply.

'The advise from the authorities are not just little hints,' he said. 'It is expected that we follow them every day, every minute.'

It's Time to Get Back to the Business of America

The United States is staring at a cinema-worthy apocalypse. You know, with feral animals eating human corpses, mutant plants reoccupying streets and buildings, empty restaurants and malls across the landscape . . .

Well, that last part is true, anyway. Not because of the disease, but rather the hysteria.

You’ve heard the apocalyptic claims. Imperial College in London estimates as many as 2.2 million U.S. deaths, depending on how drastically the population is locked down, locked out, and locked in. To reduce that figure to a “mere” 1.1 million, we would need to live a maximum-security lifestyle “until a vaccine becomes available (potentially eighteen months or more),” they said. The CDC has issued an estimate of as many as 1.7 million American deaths.

Yet with lesser measures in place now—and for a very short period—the market has crashed, unemployment claims are being filed at levels unseen since the height of the Great Recession, and there looms a real possibility of a worldwide depression. Yet there are those who say such measures aren’t nearly draconian enough.

Do we really need to destroy the country to save it?

Consider that China was taken completely unaware by the virus and, with an unfit healthcare system and poor public hygiene, has so far reported fewer than 3,300 deaths. Their epidemic peaked over five weeks ago with almost no new cases now. Based on the above predictions, despite a vastly better healthcare system, the United States can expect a per capita death rate about 2,500 times higher than the Middle Kingdom. Seriously, Imperial College?

You could quit reading right there. But please, don’t. The utter insanity here is worth documenting. It’s also worth knowing why even the low-end U.S. estimates are nonsense.

The pandemic is showing signs of slowing worldwide. And that was to be expected per what’s called “Farr’s Law,” which dictates that all epidemics tend to rise and fall in a roughly symmetrical pattern or bell-shaped curve. Ebola, Zika, SARS, and AIDS all followed that pattern. So does the seasonal flu each year. Peaks for COVID-19 have already been reported in China, South Korea, and Singapore.

Importantly, Farr’s Law has precious little to do with human interventions such as “social distancing” to “flatten the curve.” It occurs because communicable diseases nab the “low-hanging fruit” first (in this case the elderly with comorbid conditions) but then find subsequent victims harder and harder to reach. Until now, more or less, COVID-19 has been finding that low-hanging fruit in new countries, but the supply is close to running out. While many people assume that the draconian regulations implemented in China are what brought the virus under control, Farr’s Law offers a different explanation. Even The New York Times admitted that South Korea recovered far more quickly with regulatory measures nowhere near the scale of China’s—although the Times still attributes that entirely to human intervention, of course, assigning no role to Mother Nature.

When the coronavirus epidemic ends and the public-health zealots inevitably slap themselves on the back for having prevented the nightmare scenarios they themselves cooked up, don’t buy it. This isn’t to say that thorough hand-washing several times a day and not sneezing and coughing in others’ faces won’t help: It will. But the authoritarian and economically devastating measures taken by the United States and other countries are wrecking the world economy. Any feared apocalypse would happen on their account, not the disease’s.

Coronavirus has not emptied our streets; government dictates have.

Right now, we’re seeing such a dramatic spike in cases because testing has only recently become readily available in the United States, due to a delay in the CDC developing its own assay. This availability has been almost universally hailed as a good thing, but it has at least two bad aspects.

First, tests will pick up many asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic people, who will be counted as “cases” just as much as those on death’s door. This will further contribute to hysteria. Second, many of those highly mild cases will suddenly develop “nocebo” symptoms (the opposite of placebo), in which negative expectations seem to cause real symptoms. This will only add to the confusion. Nocebo symptoms are psychosomatic but can feel very real. They can definitely mimic COVID-19 symptoms like fatigue and shortness of breath. It’s a good guess that hospitals are already seeing their share of the “worried well,” people who were feeling more or less okay before they tested positive and suddenly feel deathly ill.

On the positive side, the more you test, the lower the death rate becomes, because the denominator grows faster than the numerator. Rather than the 3.4% rate the WHO touted in early March, the crude U.S. death rate is about 1.35%. As testing continues, the rate will drop even further.

So how many deaths can the United States reasonably expect? From what the media tell us, “Italy’s Coronavirus Crisis Could Be America’s.” Really?

That country so far has had just over 7,500 deaths out of a population of 50 million, but the number of new cases and the number of deaths per day have peaked, with the highest number coming on March 21.

Still, at this point that’s a stunning 10% crude death rate, by far the highest death percentage in the world, which of course is why the media choose to focus on it almost exclusively. Germany, by contrast, has only about 240 deaths out of a much larger population.

But why is this happening in Italy? Partly because Italy simply doesn’t have a great health care system. Last year, the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security ranked the United States the best prepared country in the world to handle a pandemic in late 2019. Italy came in thirty-first place.

As Forbes recently noted, U.S. hospitals have vastly more critical care beds per capita than Italy, which in turn has more than South Korea. And you don’t even want to hear about China. Bed pretty much equals floor.

Beyond that, Italy also has the fifth-oldest population in the world; the United States ranks sixty-first. We already knew from data released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control that COVID-19 preys overwhelmingly upon the old and infirm, with death rates dramatically higher for those aged seventy and older. Further, almost all the elderly dead in that study had “comorbid” conditions of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hypertension.

Similarly, a March 17 study in Italy found that the vast majority of those who had died in that country thus far were over the age of seventy, and virtually all had comorbid conditions; in fact, half of those who died had three or more. Almost nobody under the age of fifty has succumbed, and almost all who have also had serious existing medical conditions. This may reveal something about Italy’s healthcare system, but it’s not a portent of America’s future.

Yet another U.S. advantage is that the disease hit here later than in Italy (and Asia, of course). Spring is in the air. Respiratory viruses usually hate warm, moist, sunny weather. Hence flu arrives in the United States in the fall and disappears by April or May. We know the “common cold” is rare in summer; many colds, in fact, are caused by different coronavirus strains.

SARS was a coronavirus and simply died out between April and July, 2003. The media and public health alarmists cite MERS-CoV as an exception, but it also flounders in warm, wet weather. Public health officials and the media desperately want you to think this coronavirus is different, but evidence so far suggests that it follows the usual seasonal patterns.

This year, the flu peaked in February. It’s possible that, even now, warmer weather is affecting U.S. coronavirus spread. Will it come back in autumn? Probably. But by then many in the population will have had exposure immunity, hospitals will be better prepared, the “worried well” problem will be diminished for lack of novelty, and we’ll have time to see if anything in our arsenal of antivirals and other medicines is truly effective. (No, there will be no vaccine available.)

Meanwhile, it’s very difficult to assess the effectiveness of the restrictive measures blanketing most of the country. We know hermits don’t get contagious diseases, but there’s a reason the term “society of hermits” is an oxymoron. South Korea didn’t need such drastic measures and Sweden hasn’t used them, even as its neighbor Norway has been praised for early implementation. For its efforts, Norway has been rewarded with twice as many cases per capita and is suddenly suffering its highest unemployment rate in eighty years.

But as always, we follow the dictates of the public health zealots, the media, and the power-hungry pols. Reality is bitter medicine; hysteria may taste sweeter at first, but it has dubious benefits.

Saturday, April 11, 2020

Proof Democrats HATE Universal Basic Income...

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) has drafted an amendment to a Republican plan that will ensure millions of very low-income, poor Americans are eligible for $1,200 or more in federal payments in the midst of the coronavirus crisis.So where are all the Progressive Democrats? They're holding up relief bills for working Americans like this instead of backing them.

Current legislation to give a quasi-Universal Basic Income (UBI) to Americans excludes those making under $2,500 or less a year. These are the lowest, poorest Americans and also American college students who do not necessarily work all year long.

Hawley’s amendment would end that income threshold and give money all Americans with a Social Security Number or Individual Taxpayer Identification Number.

“Relief to families in this emergency shouldn’t be regressive,” Hawley wrote online. “Lower-income families shouldn’t be penalized.”

Cash to Americans — a plan originally touted by businessman Andrew Yang as a permanent program that would replace all existing forms of welfare — was most recently touted by Breitbart News’s Economic Editor John Carney, who called on Congress to implement a policy in which every American, including those earning over $75,000 a year, are sent the payment:

We need to put cash into the hands of the American people as quickly as possible.Millions of American workers have been forced to stay home from their jobs, as restaurants, bars, and other businesses have been required to close in many states.

I propose $1,000 of cash for every U.S. citizen. A family of four gets $4000 per month for the duration of the crisis. Bigger families get more. This boost of income will allow Americans to build emergency savings without having to drastically cut down on their spending.

This will not stop all the job losses but it will make them less painful. More importantly, it will make it far less likely that we go from stage one to stage two. It will make it more likely that the economic emergency can be contained to frontline effects.

These service industry workers generally rely on tips and minimum wage to pay their rent, mortgage, and other monthly bills. Often, they have no longtime financial security in place to tap into during emergency situations.

In total, the latest JPMorgan Chase analysis finds that about one-in-four American families do not have any savings and nearly half of Americans would struggle to pay $400 to cover an emergency.

Thursday, April 9, 2020

Monday, April 6, 2020

Planning for the Next Pandemic...

President Donald Trump downplayed the coronavirus threat, was slow to move and has delivered mixed messages to the nation. The federal bureaucracy bungled rapid production of tests for the virus. Stockpiles of crucial medical materials were limited and supply lines cumbersome. States and hospitals were plunged into life-or-death competition with one another.

When the public looked to government for help, government sometimes looked helpless or frozen or contradictory - and not for the first time.

The country and its leaders were caught off guard when terrorists on hijacked airplanes attacked the homeland on Sept. 11, 2001. The financial crisis of 2008, which turned into a deep recession, forced drastic, unprecedented action by a government struggling to keep pace with the economic wreckage. The devastation from Hurricane Andrew in Florida in 1992 and Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005 exposed serious gaps in the government's disaster response and emergency management systems.

"We always wait for the crisis to happen," said Leon Panetta, who served in government as secretary of defense, director of the CIA, White House chief of staff, director of the Office of Management and Budget and a member of the House. "I know the human failings we're dealing with, but the responsibility of people elected to these jobs is to make sure we are not caught unawares."

In interviews over the past two weeks, senior officials from administrations of both parties, many with firsthand experience in dealing with major crises, suggest that the president and his administration have fallen short of nearly every standard a government should try to meet.

Repeated crises have shown that government is rarely, if ever, fully prepared. Nor is government as flexible as it needs to be to respond as quickly or creatively as conditions often demand. Many factors contribute to what appear to be chronic weaknesses that can compound problems and reduce public confidence. Lessons learned after the fact solve past problems without necessarily anticipating future ones.

Leadership is important, and President Donald Trump will have on his record what he did and didn't do in the early stages of this particular crisis. But the problems go far broader and deeper than what a president does. Lack of planning and preparation contribute, but so too does bureaucratic inertia as well as fear among career officials of taking risks. Turnover in personnel robs government of historical knowledge and expertise. The process of policymaking-on-the-fly is less robust than it once was. Politics, too, gets in the way.

Long ago, this was far less the case, a time when the United States projected competence and confidence around the globe, said Philip Zelikow, a professor at the University of Virginia who served in five administrations and was executive director of the 9/11 Commission.

"America had the reputation of being nonideological, super pragmatic, problem solvers, par excellence," he said. "This image of the United States was an earned image, of people seeing America do almost a wondrous series of things. . . . We became known as the can-do country. If you contrast that with the image of the U.S. today, it's kind of depressing."

- - -

Government officials have worried about the threat of a pandemic like the coronavirus for many years. In the fall of 2005, President George W. Bush tasked Fran Townsend, his homeland security adviser, to develop a national pandemic strategy. What prompted the directive was not an imminent threat to which he had been alerted by advisers; it was because he had read John Barry's book, "The Great Influenza," about the flu pandemic of 1918.

Townsend recalled that when she convened an interagency meeting to launch the project, she met significant resistance from Cabinet officials who said they had far more urgent problems to deal with. Only with prodding and presidential insistence did the pandemic strategy get put together, and it was part of the Bush team's handoff to the administration of Barack Obama during that transition.

The Obama administration ended up dealing with a series of virus threats, and that experience shaped the transition handoff to the Trump administration three years ago.

On Jan. 13, 2017, Lisa Monaco, who was White House homeland security and counterterrorism adviser in the Obama administration, convened a meeting in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. The session brought together the members of the outgoing Obama Cabinet with the Cabinet designees in the incoming Trump administration.

Attendees included the outgoing and incoming secretaries of homeland security, Jeh Johnson and John Kelly, who later became White House chief of staff. Tom Bossert, who was to be Monaco's successor as White House homeland security adviser and who has since left the Trump administration, acted as co-chair.

The session dealt with terrorism and cyber and various other threats, but because the Obama administration had been through H1N1, the Ebola crisis and the Zika virus, Monaco included a discussion of what she regarded as the nightmare scenario: a new strain of flu that was a respiratory illness for which there was no vaccine and that because of globalization and travel patterns would be nearly impossible to contain.

"I don't want to give an impression that we bestowed the answer key for dealing with such a challenging and unprecedented crisis," Monaco said. "But the idea was to identify issues that would say these are the kinds of things you need to be planning for and thinking about now."

What does it mean for the federal government to be prepared? "Oftentimes, the gauge is no mistakes, no criticism, just complete smooth sailing," Monaco said. "That to me is not the definition of what it means to be prepared."

She argued that preparation means planning ahead of a crisis, and having structures and organizations that can move quickly and principles that guide decision-making. "I think it's about trying as best to minimize the chaos, particularly at the beginning," she said.

Almost by definition, a crisis is something no one has or can prepare for fully. As Zelikow put it, what government is least prepared for is to do things "different from what it did yesterday." Then the question becomes whether government is agile enough to figure out what to do next. On that measure, the record is not encouraging either.

Joshua Bolten, who served as White House chief of staff in the administration of George W. Bush, said, "It's especially hard for government to be prepared for the unexpected or the unpredicted. That was certainly true in 9/11. When you think back to 2001, if you had said that, while it looks like there's enhanced risk of terrorist activity in the United States, I don't know that you necessarily would have checked on who was enrolling in flight schools."

- - -

It isn't that government doesn't do planning. The Pentagon has contingency plans for wars, conflicts and disasters - "for anything everywhere . . . for everything," as Panetta put it. But federal domestic agencies don't have the same culture as the Pentagon.

"The Pentagon bureaucracy has the resources to do that. There's a deputy secretary for everything," said Johnson, who served as general counsel at the Pentagon before going to DHS. "Homeland security is a relatively new concept. The headquarters bureaucracy at DHS is still a work in progress."

But plans by themselves are not a measure of preparedness. When Stephen Goldsmith, a professor at Harvard's Kennedy School, was deputy mayor of New York, his portfolio included emergency management. When he would ask about potential disasters, "They'd take out a black three-ring notebook and they'd say, 'We have a three-ring notebook for that.' " That was only partially reassuring, he added, "because the chances of something happening not in a three-ring notebook is really high."

Goldsmith assesses the situation this way: "I think we've gotten relatively good as a country - local, state and federal government - at the professional performance of routines. Our ability to accomplish the important routines of government on a daily basis is very high."

But there are limitations, he said. "One is, are they conducive to imagination? Second, do they value the exercise of discretion throughout the system? And third, are they good at calculating the risk across agencies? What are the trade-offs of closing a country?"

The culture of plans on shelves can carry government officials only so far when disaster strikes. What then becomes more important are the systems in place that allow for quick action, improvisation and the rapid creation of systems to deal with the unexpected.

Andrew Card Jr. was secretary of transportation in the administration of President George H.W. Bush. When Hurricane Andrew hit Florida and there was criticism of the federal response, Bush tapped Card to go to Florida and take charge. He spent seven weeks there.

He found resistance within the bureaucracy to bend the rules. "I found that FEMA is a great organization, but they were all afraid to do things that weren't, quote, by the book," Card said. "FEMA was always being challenged . . . second-guessed after a disaster."

Card learned through that experience and later as White House chief of staff to President George W. Bush during 9/11 and Katrina the obstacles that the combination of fear and bureaucratic inertia can impose when immediate and innovative action is required.

"Each bureaucracy has its own momentum," he said. "The challenge in dealing with a disaster is addressing the momentum or the inabilities. If something's not moving, it takes a lot of effort to get them to move."

Lack of integration - public health with emergency management with economic assistance - across the government creates other obstacles. So too does turnover in personnel or vacancies in key positions, which has been a continuing problem particularly in this administration.

"If you do not have people who do not remember the lessons learned and you don't have people who have navigated these enough to have relationships across the government, you can be hampered," said Mark Harvey, former senior director for resilience policy at the National Security Council. "You never want to be exchanging business cards at a disaster scene."

Andrew Natsios, a former administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development and current director of the Scowcroft Institute at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University, said time is the most precious asset when dealing with disaster. "How fast you move will determine whether you control the course of events or whether you lose control," he said.

Even presidents are constrained in their power to make things work. No president is fully capable of managing a crisis, which means having to rely on leaders in agencies who can help implement policies on the fly. In this moment, Trump is hampered by not having fully staffed the political positions across the government and by rhetoric that has denigrated career officials.

"President George H.W. Bush had more control over the federal bureaucracy than any president in the last 40 years," Natsios said. "He developed a large following of loyal people. He had control so when he gave an order we did it. When I got an order from the White House, I did it. Part of his effectiveness was appointing people to control this very complex federal system that tends to ignore the president."

The Trump administration has been particularly weak in that regard, with scores of long-standing vacancies in critical positions, hostility toward career officials who are vitally important in times like these and with an indifference to the importance of selecting competent political appointees, rather than presidential favorites, that began during the transition and has plagued the government ever since.

Success goes beyond a president's capacity to engage and move the bureaucracy. A top-down system inhibits quick action when needed. Experts in disaster management suggest that a functional system empowers officials farther down in the government to act without having been ordered to do so. Coordination must be at higher levels of government; response should be at a much lower level.

- - -

No plan survives its first brush with reality. What worries some people who have studied the issues of preparedness and government action is a long-term deterioration in the federal government's capacity to do large-scale, improvised planning.

"It doesn't mean it's now uniformly bad, it varies. But the quality has deteriorated," Zelikow said. "I think we've some illustrations in this crisis and I think we'll see more, I'm sorry to say. People who want to can always turn these into partisan arguments, and there are some particular individuals one can criticize. But there are deeper problems at work."

Zelikow pointed to an earlier era when the world looked at the United States as being capable of almost anything. He cited the Marshall Plan that helped save Europe after World War II and creation of the Berlin Airlift in 1948 when the Soviet Union shut off ground access to Berlin, which threatened the well-being of residents there. In that case, improvisation quickly turned into a system that eventually forced the Soviets to relent and reopen the city.

One case where such policymaking worked better was in the Bush White House after 9/11. Bush ordered the creation of a domestic consequences policy committee to oversee economic and other issues that needed to be dealt with, apart from responding to the terrorist threats, from reopening financial markets to putting airplanes back in the skies to compensation for families of victims.

"It certainly wasn't smooth, but I recall that process working reasonably well," said Bolten, who was White House deputy chief of staff at the time and chaired the committee. "People knew who the decision-makers were and where to go, both short of the president and how to get to the president on a decision."

The Obama administration earned generally good marks for the way officials dealt with the Ebola crisis in 2014, consolidating decision-making under one person, Ron Klain, who had previously served as vice presidential chief of staff. He later recommended that he be the last disease-specific czar, that government needed a permanent expertise within the White House.

Improvisation in the midst of a crisis requires one set of skills, both in terms of leadership and the capacity for creative policymaking. "It's really hard for government to understand every different collateral consequence that will occur until you start to experience it," said former New Jersey governor Chris Christie, whose state was devastated by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

But how can government prepare for the next crises, which seem to come at a faster and faster pace? As Harvey noted, "This is a once-in-a-century event. We're also at the point where this is our fifth or sixth once-in-a-century event in the last few years. Wildfires in California. Hurricanes in Caribbean and the Southeast. Floods in Midwest. Volcano in Hawaii and now this. Even before covid-19, we were in the midst of spending $149 billion on eight simultaneous large-scale recovery efforts when we'd only done one at a time before."

- - -

Planning for the next crisis takes money. Political leaders know there are rewards from citizens for successful response to a disaster but little support for taking preemptive action, especially when the cost is high.

"Governments have a very hard time securing money, for spending money for things that might not happen," said Kathleen Sebelius, secretary of health and human services in the Obama administration and former governor of Kansas. "So any time that we are preparing for an unknown, to secure that in a tight budget year, to make sure dollars are set aside, was a battle in my time of government. There was always a more pressing priority."

Even if the money is available, determining how to spend it can defeat the purpose of having it. As threats of terrorism were growing in the late 1990s, the intelligence community sought more money, but the funds were distributed without a strategy or clear priorities, such as building up Arabic-language skills within the government.

"If you examine the pre-9/11 run-up and how well government adapted to rising of terrorism," Zelikow said, "the fundamental institutions adapted hardly at all. I think this is partly because this is not a partisan issue. It transcended both Democratic and Republican administrations."

The absence of capacity for real planning could be especially damaging in the context of a threat farther out on the horizon. Tyler Cowen, a professor of economics at George Mason University, looks at what has happened with the coronavirus pandemic to speculate about how the government might deal with threats from climate change.

"In the United States, as you know, we had a solid two months' warning and did nothing. And even now, in terms of getting testing and masks set up and the like, there are incredible delays," he said. "So we might finally overcome those problems. But, you know, with climate change, you need a 20-to-30-year ramping up for it to work."

Cowen said it's inexplicable why the federal government, given all the warnings and evidence from China of a spreading pandemic, did not move more rapidly.

"You know, Trump was terrible, but you can't just pin it on him. It's far more systemic than that. The NBA [which suspended its season on March 11] really gets so much credit. I would put the NBA in charge of fighting climate change at this point."

"The question for me is, does government retain a certain baseline level of preparedness . . . and then whether government is nimble and agile enough to take a baseline and put it on steroids when something occurs," said Janet Napolitano, former secretary of homeland security in the Obama administration.

The performance by the Trump administration and the government as a whole in responding to the coronavirus pandemic will be thoroughly examined. The president's handling already is a focus of criticism, and his reelection could hinge on how the public assesses his leadership next November. A national commission similar to that which was created after 9/11 could follow with a thorough exploration of what has happened.

Lessons will be learned and changes will be made, as they have after other disasters. Anyone looking for a few simple fixes - a fuller stockpile of material, more funding for public health, a designated agency to deal with the next new virus - will quickly find themselves disappointed. Those changes alone, however needed, will not have solved the underlying problems of a governing and political culture that, for all the good they can do when called upon, have limits, especially when officials are caught unawares and forced to act in new and unfamiliar ways.

"I've often wondered if democracy writ large is designed to be responsive rather than preemptive," said Tom Ridge, the nation's first secretary of the Department of Homeland Security. "One of the lessons perhaps as a result of this is we'll be a little more inclined to be preemptive. With election cycles every two years, there is not a lot of credence given to people who take a longer view."

Wednesday, April 1, 2020

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)