Politics turned Parody from within a Conservative Bastion inside the People's Republic of Maryland

Saturday, December 28, 2019

Tuesday, December 24, 2019

What Intellectual Integrity on the Left Looks Like...

Tulsi Gabbard has been slowly edging toward leaving the Democratic Party and, it now seems more likely than not, launching a spoiler candidacy to peel disaffected left-wing votes away from the Democrats. Her “present” vote on impeachment, followed by a disavowal of what she called the “zero-sum mind-set the two political parties have trapped America in,” sets the stage for Gabbard to play the role of 2020’s Jill Stein.

Left-wing anti-anti-Trumpism played an important role in the bizarre 2016 outcome. Die-hard Bernie activists, fired up with anger at the release of DNC emails stolen by Russians that purportedly showed the party had rigged the primary, demonstrated against the party outside its convention hall and tried to drown out the speakers inside with boos. Stein attacked Hillary Clinton from the left, then audaciously staged a grift-y fundraising scheme supposedly to hold recounts in the states she had labored to flip to Trump. Trump’s election appeared to deliver the same shock of reality that had vaporized Ralph Nader’s 2000 support.

But Gabbard’s emergence is another indication that the disaffection that drove these events has not disappeared. Anti-anti-Trumpism has maintained a small but durable intellectual infrastructure. The sentiments that first registered as dissent from the Russia investigation transferred to impeachment, and a chorus of left-wing voices is attacking the effort to remove Trump from office as at best a misguided diversion and at worst a deep-state coup.

The anti-anti-Trump left is not a monolithic bloc. It has differing levels of enthusiasm for splintering the progressive vote in general elections, for Trump himself, and for the ethics of explicit alliances with the right. (Some anti-anti-Trump leftists eagerly appear on Fox news and other right-wing media, while others shun it.) What they share, in addition to enthusiasm for Bernie Sanders, is a deep skepticism of the Democratic Party’s mobilization against the president. The left’s struggle against the center-left is the axis around which their politics revolves. From that perspective, the Russia scandal and impeachment are unnecessary and even reactionary.

While incomprehensible to liberals, centrists, and even many leftists who work within two-party politics, left-wing anti-anti-Trumpism has a coherent logic. It takes as its starting point a familiar critique that Trump won because liberalism failed. Trump, while bad, is merely a meta-phenomenon of the larger failure of the Democratic Party and the political and economic Establishment. And so, to the extent that investigating Trump’s scandalous behavior allows Democrats to discredit Trump without undergoing revolutionary internal changes, it is counterproductive. “The Ukraine affair,” writes left-wing historian Samuel Moyn, “shows that the biggest risk to the American people is that centrists link impeachment to a reinstatement of one set of failed prescriptions, while the right repulses the attempt to oust the president and rules under equally dead-end policies.”

Some anti-anti-Trump leftists see impeachment not merely as a distraction from the Sanders revolution but a deliberate effort to marginalize it. Krystal Ball and Aaron Mate recently speculated that Democratic leaders just might be setting up an impeachment trial in order to keep Sanders and Elizabeth Warren locked up in Washington and off the campaign trail. While such a possibility is obviously insane, if you consider the struggle between left-wing populists and evil neoliberals to be the central dynamic in American politics, it might seem at least plausible.

What gives the anti-anti-Trump left its emotional impetus is a simmering resentment against the center-left, especially the way the Russia and Ukraine scandals have made Democrats lionize elements of the security Establishment. “My discomfort in the last few years, first with Russiagate and now with Ukrainegate and impeachment, stems from the belief that the people pushing hardest for Trump’s early removal are more dangerous than Trump,” writes Matt Taibbi.

Ted Rall, who has been given space on The Wall Street Journal op-ed page to publish periodic anti-anti-Trump columns, uses one of his recent pieces to quote Doug Henwood, a fellow leftist. “It seems like a lot of Dems think that everything was pretty much OK until Trump took office, and if we can just get back to the status quo ante, everything will be all right,” Henwood says, “Add to that the fact that impeachment is making liberals celebrate spies, prosecutors, and heavily medaled soldiers — people no one on the left should have any warm feelings towards — and you get a serious feeling of derangement.”

This is less an argument than an expression of mood. The scandals have reordered the contestants in the political drama in a way anti-anti-Trump leftsists simply can’t stomach. The spectacle of Democrats lionizing intelligence officials and other cogs in the security state creates an irrepressible gag reflex.

Ironically, the same dynamic has brought anti-anti-Trump leftists into their own strange-bedfellow alliances. Leftists like Mate and Glenn Greenwald sometimes appear on Tucker Carlson’s show, giving an edgy, trans-ideological sheen to his increasingly overt white nationalism. Ball’s “Hill.TV” outlet was started by John Solomon, the Republican operative who has worked closely with Russian oligarchs to disseminate conspiracy theories that vindicate both Trump and the Russians. Its format frequently consists of Ball and her conservative co-host alternating attacks on the Democrats from the left and the right.

The fact that anti-anti-Trump leftists have interests that coincide with Russia’s compounds the dynamic. There is zero reason to suspect any of them have covert ties of any kind with Russia. Their arguments are perfectly explainable in normal terms. Russia has helped amplify their ideas because it suits Russia’s agenda — Moscow generated and promoted the most strident anti-Clinton voices on the left in 2016 and seems to view left-wing opposition to the Democrats as a lever upon which it can usefully lean. That fact does not by itself implicate their arguments; if the Russians happened to find reason to promote arguments any of us have made, we’d resent people suggesting we were toeing the Kremlin line. That resentment seems to have created a life of its own, making some leftists tolerant of Trump’s disturbing, obviously corrupt relations with Putin.

But what brought them to this strange place is their hatred for the center-left, which blots out any sense of proportion of the danger Trump poses. Pay close attention to this sentence, by Samuel Moyn, especially his use of the operative terms equally and biggest risk: “The Ukraine affair shows that the biggest risk to the American people is that centrists link impeachment to a reinstatement of one set of failed prescriptions, while the right repulses the attempt to oust the president and rules under equally dead-end policies.” The right and the center-left are equally doomed, and the biggest risk is that the Establishment prevails over Trump.

Many leftists can imagine a bigger risk than the Establishment neutralizing Trump before he can bring the system down. Yet somehow, the emergency of his growing authoritarianism has not concentrated every mind, and the election of Trump has not dispelled the fantasy that his destruction of the center and the center-left will lead ultimately to a better world.

Wednesday, December 18, 2019

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Friday, December 13, 2019

Thursday, December 12, 2019

A Return to Class Distinctions...?

Since at least 2016, the divide between the “working class” and the “elite” has been considered a defining issue in American (and Western) politics. This divide has been defined in occupational terms (“blue collar” versus “information workers”), geographic terms (rural and exurban regions versus major urban cores), and meritocratic terms (non-college-educated versus those with elite credentials). Occasionally, it is given an explicitly moral connotation (“somewheres” versus “anywheres,” “deplorables” versus “cosmopolitans”). All of these glosses effectively track basic economic categories: those who are seen to have enjoyed success in recent decades and those who have been “left behind.”

Like most clichés, this one contains elements of truth. The working class has experienced economic stagnation and precarity, and even declining life expectancy in the United States, as well as lower family stability and civic engagement. Social mobility has declined, while inequality has widened.

But it is precisely for these reasons that the working class is unlikely to be decisive in shaping politics for the foreseeable future. However one defines the working class, it has scarcely any political agency in the current system and no apparent means for acquiring any. At most, working-class voters can cast their ballots for an “unacceptable” candidate, but they can exercise no influence on policy formation or agency personnel, much less on governance areas that have been transferred to technocratic bodies. In countries like France, the working class might still be able to veto certain policies through public demonstrations, but such actions seem unlikely in the United States, and even the most heroic efforts of this kind show little prospect of achieving systemic reforms.

For regimes that style themselves liberal democracies, this situation might be disconcerting, yet it has persisted for some time. The policy agenda that brought about the political and economic marginalization of the working class was adopted between the 1970s and the early 2000s. A more organized working class was unable to stop it then; it is difficult to imagine a weakened working class reversing it now.

While a restive working class might provide fertile ground for political upheavals, any fundamental transformation of Western politics will necessarily be led by increasing numbers of the “elite” who defect from the dominant policy consensus and rethink their allegiance to establishment paradigms. Conventional narratives, including many that are critical of the status quo, paint the elite as a unified block aligned with neoliberalism. But the neoliberal economy has created a profound fracture within the elite, the significance of which is just beginning to be felt.

The socioeconomic divide that will determine the future of politics, particularly in the United States, is not between the top 30 percent or 10 percent and the rest, nor even between the 1 percent and the 99 percent. The real class war is between the 0.1 percent and (at most) the 10 percent—or, more precisely, between elites primarily dependent on capital gains and those primarily dependent on professional labor.

The last few years have brought about a new “discovery” of working-class immiseration—a media phenomenon arguably provoked by renewed elite anxieties. As a result, the story of a declining working class is now broadly understood. It is, after all, decades old, and it was entirely predictable if not exactly intended. Much less understood, however, is the more recent reshaping and radicalization of the professional managerial class. While the top 5 or 10 percent may not deserve public sympathy, their underperformance relative to the top 0.1 percent will be more politically significant than the hollowing out of the working or lower-middle classes. Unlike the working class, the professional managerial class is still capable of, and required for, wielding political power.

At bottom, the economy that has been constructed over the last few decades is nothing more than a capital accumulation economy. As long as returns on capital exceed returns on labor, then the largest capital holders benefit the most, inequality rises, and wealth becomes more and more narrowly concentrated.1 Labor—including elite labor—is inevitably left behind. Marxian thinkers have been analyzing these dynamics for almost two centuries, but they have often misread the political effects of these developments, which play out primarily among the elite managerial class, rather than within the binary of capitalists and proletarians.

The Forgotten Managers

Discussions of stagnant wage growth for nonmanagerial workers since the 1970s have become commonplace over the last few years, along with the story of hardening socioeconomic divides.2 “The 9.9 percent is the new American aristocracy,” as one Atlantic headline put it.3 Yet what is happening within the 9.9 percent has received little scrutiny. In fact, the fortunes of the members of this new “aristocracy” have diverged considerably. The performance gap between the top 1 or 0.1 percent versus the top 10 percent is actually larger than the gap between those right at 10 percent and any part of the bottom 90 percent.

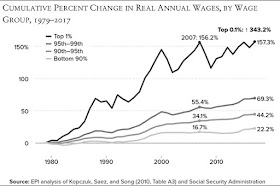

Members of the top 5 or 10 percent have done better than the middle and working classes in recent decades, but this masks their dramatic underperformance relative to the top 1 percent (and especially the top 0.1 percent). Since 1979, the real annual earnings growth of the top 1 percent has more than tripled that of earners at 10 percent, while growth for the 0.1 percent is, in turn, more than twice that of the 1 percent.

The picture is even darker when the elite category is expanded. Senator Ben Sasse, for example, drawing on Robert Putnam, has defined the “mobile educated elite” as the top 31 percent.4 But the top 1 percent has left the rest of this group far behind. According to the Congressional Budget Office, income grew 226 percent after taxes and transfers from 1979 to 2016 for the top 1 percent, but only 79 percent for the next 19 percent of Americans, and significantly less—47 percent—for the middle 60 percent.5 Whatever their cultural aspirations, the economic trajectory of someone at 31 percent is closer to that of the 61 percent than the 1 percent.

In addition, the year 2000 represented something of an inflection point for high earners—just as Chinese accession to the WTO around that time was a tipping point for manufacturing workers. After 2000, growth began to slow for all income groups, though massive inequality persisted. By contrast, from 1980 to 2000, incomes were growing at a healthy pace throughout the top 10 percent. Whatever the benefits of neoliberalism might have been, they were exhausted for all but the largest capital holders by 2000.

Lost amid the celebrations of the “information economy” in recent decades is the fact that elite career trajectories are no longer what they used to be. The performance gap of elites versus the working and middle classes has widened, but professionals outside the very top are unlikely to match the wealth accumulation of their parents.

Big Law, for example, has recovered from the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, when articles proclaiming the death of that business model were being written every week.6 But the sector has still undergone some lasting structural austerity, particularly at the associate level, and remains far from its “golden age.”7 Associate salaries at white-shoe firms, for example, remained flat from 2007 to 2016.8 They began rising during the last two years, but analysts are already seeing industry demand slowing again.9

Finance is another sector that no longer delivers for the top 5 percent like it once did, even though firm profits are high. At Goldman Sachs, according to Bloomberg, “Compensation per employee is down 61% . . . when adjusted for nominal wage growth in the period [since 2007].”10 Some of this decline is related to Goldman’s move into retail banking, but not all of it: “Traders have been the worst hit as trading isn’t what it used to be,” noted an analyst quoted in the Bloomberg report. Average compensation for mid-level employees in sales and trading has fallen by about half while investment banker salaries have been reduced by about one-third.11

Outside of the banks, hedge fund returns have been disappointing for decades. Of the thousands of funds that exist today, no more than a handful have any reason to exist. Accordingly, fees have been falling across the industry for several years.12 Typical employees can enjoy a comfortable lifestyle, to be sure, but they are unlikely to accumulate substantial capital themselves—certainly nothing equivalent to what their counterparts in the 1980s and ’90s achieved. Even at the very top, the latest generation of celebrity managers, such as Bill Ackman, David Einhorn, and Dan Loeb, have mostly fallen flat. They will never match the records of the older generation of stars who got their start in the Reagan era—though many of these managers have also sputtered. Private equity is comparatively healthier, but it has become highly competitive and increasingly reliant on financial engineering gimmicks, such as selling companies between funds managed by the same firm.13 In short, the effects of financialization on the real economy are being replicated within the industry itself—the upward redistribution of rents within a context of overall deceleration.

Silicon Valley, meanwhile, continues to be seen as the brightest star in the new economy universe. For founders and venture capitalists, it would be difficult to imagine a better system for minting billionaires—even if today’s most celebrated start-ups, like Uber and WeWork, increasingly look like attempts to subsidize revenue growth at a loss in order to pursue monopoly rents, although with dubious prospects.14 But the Valley has never been particularly fertile for the salaried professionals and “engineers” hired by these companies, who even now generally make less than their counterparts on Wall Street or in Big Law. Kindergarten playroom office spaces and other exaggerated perks often serve to distract employees from this harsh reality.15 The median salary for U.S. IT workers, who frequently must live in high-priced urban areas, is only $81,000.16 Moreover, increasing numbers of engineers, even at the most prestigious companies, are hired on temporary contracts. When the artificial growth model stalls, employees can expect mass layoffs, “anti-hierarchy” propaganda notwithstanding. Companies like Uber and WeWork are the most prominent cases recently, but employees at many oft-hyped tech companies report surprisingly high anxiety about job security: more than 70 percent of Tesla, eBay, and Snapchat employees said they were afraid of being laid off, according to one survey released this year.17

Other professionals often fare worse. Many positions that require advanced degrees, large student loans, and living in expensive cities barely pay $100,000 a year. The streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts, are filled with large numbers of scientists with doctorates from prestigious universities working at top biotech firms or research institutes, but living seven to a house with little hope of accumulating savings. The career prospects of journalists and academics—ironic casualties of the “information economy”—are declining even more relentlessly. When members of these professions write about embittered working-class Trump supporters in declining industries, they may as well be writing about themselves. Indeed the conspicuous embrace of “elite values” by journalists and academics is often little more than an aspirational attempt to remain connected to an economically distant elite—just as educated millennials’ conspicuous consumption of “experiences” often serves as a necessary distraction from the grim reality that most will never be able to own a home.

The Rising Costs of Elite Membership

Meanwhile, the costs of maintaining elite status—and passing it on to one’s children—have risen disproportionately for the top 5 or 10 percent. The ongoing decline of the middle and working classes may have reinforced the top 10 percent’s sense of elite status, but it also means that any backsliding would be catastrophic. These pressures have converged in two key areas in particular: real estate and education.

The narrowing of economic opportunity into a smaller number of sectors and geographies (partly due to deindustrialization) has resulted in a clustering of elites into a handful of “superzips.” Even among those who have managed to do well in the heartland, their children will most likely leave for New York, San Francisco, or a handful of other cities. They often have to in order to achieve the same earning potential as their parents. Real estate prices in these areas have risen accordingly. A study by the Brookings Institution showed that the median income rose by 26 percent in San Francisco from 2008 to 2016, but rents more than doubled during the same period.18 Because of rising real estate costs, households earning in the top 25 percent nationally are actually classified as “low income” in San Francisco. The household “low income” threshold in the Golden Gate City is now approximately $117,000.19 By comparison, a household needs to earn about $100,000 to make it into the top 31 percent nationally; the national top 10 percent household income threshold is approximately $178,000.20

In addition to deindustrialization and sectoral clustering, financialization and rising intra-elite inequality added further pressure. The immediate effect of global oligarchs buying investment properties and pieds-à-terre in prime urban areas was to price out professional elites. These displaced elites then began gentrifying working-class and middle-class neighborhoods. An entire “creative class” ideology was constructed to explain this phenomenon, but its intensity simply concealed the desperation of second-tier elites to assuage their status anxiety. In reality, they simply could not afford to live in the areas where people of their status used to live, just like the working-class people whom they were, in turn, pushing out even further. On the other hand, in areas that were casualties of deindustrialization, many elite neighborhoods steadily declined.

At the same time, the costs of passing elite status onto one’s children—elite education—rose rapidly. Between 1973 and 2013, tuition costs rose faster than even the 1 percent’s income growth—and more than twice the rate of the top 5 or 10 percent’s income growth.21

The 2019 “Varsity Blues” college admissions scandal offers a unique window into the pressures that educational credentialing is creating even at the top levels of the elite. The scandal involved a number of wealthy parents bribing college coaches to get their children into prestigious universities through athletic recruiting, along with fraudulent test scores. The orchestrator of the scheme described the process as a “side door”—in contrast to the “front door” (students getting in on their own) and the “back door” (families making large donations to the university).22 It should surprise no one, of course, that elites are using their wealth to allow their children to cut to the front of the line. American meritocracy has been a sham for a long time. Rather, what is new about this scandal is the fact that a former CEO of pimco, a managing partner and founder of TPG Capital, and the cochairman of Willkie Farr and Gallagher felt compelled to use the “side door,” presumably because they could not afford the “back door.” Whatever else the scandal says about elite universities circa 2019, it reveals the seedy depths of intra-elite inequality and competition.

Moreover, while the costs of education have risen, since 2000 the rewards have been declining. During the 1990s, the wage premium for college education grew significantly. From 2000 to 2014, however, wages for young college graduates actually fell.23 In recent quarters, wages for lower-income workers are growing faster.24 These trends, combined with real estate trends, have led to more college graduates—28 percent—living with their parents than ever before.25 (The numbers are around 40 percent in New York and Los Angeles.)

Upper-Middle-Class American Radicals

Since 2000, the combination of stagnation, widening inequality, and the increasing cost of maintaining elite status has arguably had a more pronounced impact on the professional elite than on the working class, which was already largely marginalized by that point. Elites outside of the very top found themselves falling further behind their supposed cultural peers, without being able to look forward to rapidly rising incomes for themselves.

This underappreciated reality at least partially explains one of the apparent puzzles of American politics in recent years: namely, that members of the elite often seem far more radical than the working class, both in their candidate choices and overall outlook. Although better off than the working class, lower-level elites appear to be experiencing far more intense status anxiety.

The election of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), to Congress offers a clear demonstration of this. Her strongest support came from comparatively affluent, “gentrifying” neighborhoods.26 Her opponent, the establishment Democrat Joe Crowley, did better in poorer areas.

Likewise, there is more “socialist” organizing in Silicon Valley27 and elite college campuses today than in working-class exurbs. Elizabeth Warren outpolls the comparative moderate Joe Biden by nearly two to one among voters with college degrees and among voters earning over $100,000 per year.28 (Bernie Sanders is near the top in both categories as well.) Many of the most aggressive proposals associated with the Left—such as student loan forgiveness and “free college”—are targeted at the top 30 percent, if not higher. Even Medicare for All could potentially benefit households earning between $100,000 and $200,000 the most; cohorts below that are already subsidized. Moreover, as Matthew Yglesias has pointed out, “In the past five years, white liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter.”29 Identity issues are often considered separate from economics, yet economic anxieties are almost certainly contributing to these trends among white liberal professionals. Whatever the underlying merits of “woke” critiques and causes might be, these postures are mainly adopted in intra-elite competition for positions and influence.

The personal trajectory of Elizabeth Warren, an avatar of this class in many ways, almost perfectly represents the political trajectory of the professional class: first they abandoned the Republican Party and then continued to move further into the left wing of the Democratic Party. Warren, in fact, is one of the few members of the professional elite to display anything close to what might be called “class consciousness.” Her 2004 book The Two-Income Trap focused mainly on the increasing pressures faced by middle-class households, and her policy remedies have grown progressively more ambitious since then. These shifts have been accelerated among younger generations, who never enjoyed the decades of growth for elites before 2000.

The recent leftward movement of the upper middle class recalls the rightward drift that occurred in the 1970s and 80s. This previous movement was arguably more decisive politically than any awakening of the infamous “middle American radicals”—political priorities are almost always set by the affluent, after all—and could also be interpreted as a response to changing economic circumstances for the professional class. In David T. Bazelon’s formulation, the shift to supply-side Republicans and neoliberal Democrats represented a “new strategy” for the professional elite. As Barbara Ehrenreich described it,

By the seventies, middle-class opportunities in domestic government and academia were shrinking. The war on Vietnam had swallowed up the War on Poverty; the incipient “tax revolt” threatened future federal activism; economic stagflation and the oil crisis seemed to herald an “age of limits.” Making up imaginary social problems and appointing themselves to solve them—which is what the neoconservatives now accused the New Class of having done in the sixties—would no longer have worked anyway. Budgets were shrinking for antipoverty programs and for the cadre of planners . . . who were supposed to design and supervise them. If the federal government and the universities were no longer expanding, it was time to find a new patron for the intellectual vanguard of the professional middle class, and the neoconservatives hoped to find one in an obvious place—the corporate elite.30Today, the opposite is true. Upper-middle-class opportunities in the corporate and financial sectors are under pressure, and these elites are slowly but inexorably returning to the state. Their interests remain distinct from those of the working class, but they are increasingly aligning with labor rather than capital.

Neoliberal Shackles

Any new realignment of the professional class, however, is complicated by the legacy of its previous turn toward neoliberalism. For this group, the embrace of markets and consumerism did not work out the way either its proponents or critics predicted.

As the New Deal economy faded, Republican neoliberalism emerged as an alternative. While this agenda required eliminating many of the bureaucratic jobs that went with the old model, Republicans offered the professional class one increasingly attractive inducement: a chance to become, essentially, financial managers in the new shareholder economy. In the 1980s, these “yuppies” contributed to two Reagan landslides.

Yet only a few years later, the Democrats under Clinton took these voters back. The Clinton Democrats left Reagan’s economic changes intact, and even accelerated them. But they gave professionals greater scope to manage “postmaterial” concerns that suited their cultural sensibilities, mainly by expanding the so-called nongovernment sector—NGOs, multilateral institutions, government-sponsored enterprises, and other organizations that received private funding for nominally public purposes. These institutions provided elite jobs and conferred prestige on the professional class, while adding a gloss of legitimacy to a financialized economy. In the Clinton era, rising neoliberal professionals acquired not just wealth but a new public power and significance, and even a new popular mythology: the Rubin-Greenspan-Summers “committee to save the world,” the slick “war room” campaign consultant, the glamorized tech “nerd.” The Republicans could only offer “greed is good” reruns, yet another book on Tocqueville, and a thin veneer of old-line WASP affectation on top of a party increasingly reliant on déclassé “values voters.”

Elite professionals flocked to the Democrats in droves and all but abandoned the Republican Party. The cost, however, was the loss of the traditional Democratic working-class base, to which the new agenda was often hostile both economically and culturally. On the other hand, “progressive neoliberalism” offered a far more effective legitimation strategy for liberating capital from political control than Reagan’s “reactionary neoliberalism” (to borrow Nancy Fraser’s terminology).31 Finance and tech billionaires began replacing unions as the most important Democratic donors, both to campaigns and to the growing network of liberal NGOs.

Thus upper-middle-class professionals who started moving leftward on economic issues in the 2000s now found themselves at odds with the Democratic Party machine they had previously constructed. Bernie Sanders illustrated this in 2016, though Obama also experienced it initially.

Sanders’s left-wing challenge to Clinton found significant support among educated, relatively affluent voters, especially younger ones (similar to Obama’s). As one 2016 Vox headline put it, “Bernie Sanders’s base isn’t the working class. It’s young people.”32 Within any given age group, the article explained, higher-income voters were actually more likely to support Sanders.

Sanders, however, has insisted on characterizing his movement as a populist protest, rather than an insurgency driven by certain disaffected segments of the elite. In both of his campaigns, he has attempted to mobilize the working class to remake the Democratic Party. But the group he primarily attracts are the most radicalized elements of the professional class (the young, academics, underemployed college graduates, and so forth). In order to mobilize sufficient numbers of the working class, Sanders would need something like the old New Deal Democratic Party machine.33 But that apparatus is vastly diminished, and the machine that does exist necessarily resists the threat Sanders poses to its survival.

In contrast, Elizabeth Warren’s campaign more explicitly appeals to the professional class, both in form and content. Directly appealing to this dominant Democratic group allows her to co-opt at least some portions of the party establishment—the apparatchiks, if not the donors. For the moment, her challenge to the Clinton status quo appears more formidable, yet her rise is still likely to strain a Democratic machine heavily reliant on billionaire funders.34 It remains to be seen whether the concessions she will need to make to preserve the Democratic apparatus will demoralize her own natural base (many of whom remain with Sanders and feel betrayed by Obama) or otherwise undermine her candidacy.

Another obstacle for left-wing upper-middle-class radicals is their own debilitating false consciousness, which easily exceeds the confusion frequently ascribed to the working class. Instead of frankly acknowledging their own professional class interests,35 they project their concerns onto the working class and present themselves as altruistic saviors—only to complain about a lack of working-class enthusiasm later. This blindness often prevents them from recognizing where their interests diverge from the purported beneficiaries of their projects and impedes their ability to effect any larger political realignment. It also exacerbates the temptation to double down on parts of the current paradigm—such as enlarging the NGO racket—which only strengthens the billionaires in the long term.

The Self-Perpetuation of Conservative Mediocrity

The Republican Party, on the other hand, faces a very different problem—the absence of any significant professional elite, which abandoned the party long ago.

From its inception, modern conservatism has opposed the professional managerial class that came to dominate business and government in the mid-twentieth century. Despite often shrill rhetoric against this “new class,” however, conservatives could never reduce its size or importance in the modern economy.36 Instead, Republican policies merely encouraged this class to shift into finance and adjacent sectors. At the same time, conservatives sought to build their own new class by setting up parallel institutions in academia, media, law, policy planning, and so on.

Initially, the new conservative apparatus was fairly successful. But institutions built on ideological conformity inevitably tend to ossify. They also tend to be populated by mediocrities who are only there because they cannot make it into the top-tier institutions. After the rest of the professional class decamped to the Democrats, this husk was all that remained of the politically active professional elite on the right. The conservative institutions became as detached and self-referential as the “postmodern” academy they criticize, and they long ago ceased to have any significant influence on broader elite discourse. Today, their main offering to new recruits is the chance to someday apply for affirmative action for conservatives.37 The result is a highly stratified and largely dysfunctional Republican Party: a few billionaires and corporate interests (mainly those who cannot fit into the more attractive progressive neoliberal program) pay their second-rate propagandists to offer a discredited and incoherent policy agenda to an increasingly disaffected voter base.

From the Republican establishment’s perspective, however, this weakness is also its strength. By repelling all professional elites except those content to be sinecurists of relatively unsavory donors, the conservative new class minimizes any internal threats to its survival, and the donors maintain total control over the party. The voters may openly despise their own party’s “establishment”; they may begin voting for “unacceptable” candidates and causes; yet, ultimately, they cannot set policy priorities or provide government personnel. If more elite professionals remained in the Republican Party, they might take advantage of voter discontent to challenge the billionaires and replace the entire decrepit apparatus. They would likely find that task much easier on the right than it is in the Democratic Party.

As it stands, however, the conservative movement can continue to lurch on as a zombified superstructure. If nothing else, it still unconsciously serves an important purpose: advancing the interests of, while providing a useful foil for, the more important billionaires in the Democratic Party.

The Alienation of Elite Labor

Professional class opposition to the political and economic status quo will almost certainly continue to intensify. Beyond economic pressures, at least two additional sources of elite anxiety will push in this direction: the emptiness of today’s professional careers and the obtuseness of the billionaire class.

As working-class jobs have become more precarious and demeaning, professional jobs have become more meaningless and depressing. Anthropologist David Graeber has defined an entire category of “bullshit jobs” and traced their proliferation throughout the corporate world and other sectors.38 In large part, these are make-work positions for professional elites that exist primarily to pad the prestige of those above them. These jobs are not simply menial or dull, and they are often well-paying, but they are utterly pointless and sometimes even internally acknowledged as such. For all the talk of market efficiency, the “information economy” has created a vast category of professionals who do nothing but copy and paste McKinsey infographics into presentations for no social or even narrowly commercial purpose.

After Graeber published his first essay on the topic, tens of thousands of readers began sending their own accounts of their experiences in these positions to Graeber and other commentators. To quote one example:As far as I could tell, very few white-collar workers at P&G really did anything. All I saw was a lot of bureaucratic box-ticking and people patting themselves on the back for work that they hired consultants to do for them. P&G as a whole really just reminded me of the trust-funders I went to college with. There was zero exposure to actual risk or competition but everyone had to pretend to be innovating and competing in order to justify their success.39And these experiences are not limited to staid conglomerates in mature industries. The reality in much of Silicon Valley may be even more depressing:The company I now work for started as a parking app. . . . We were growing sustainably as the result of having a superior product based on a great understanding of consumer needs.Contrary to the pervasive mythology of entrepreneurialism and creativity, it is glaringly obvious to today’s professional elite that the neoliberal economy is allocating capital, and especially talent, very poorly. The conclusion of one recent empirical study of corporate law firms—“greater amounts of work that associates consider more interesting is negatively correlated with firm profitability”41—could be applied across most elite job categories. This state of affairs is not only disorienting to professionals indoctrinated to believe that their career should be their “passion.” It also foreshadows further economic pressure on their class when the next recession, the increasing automation of white-collar jobs, and the logic of shareholder primacy all take their toll.

But sustainable growth isn’t what VCs (or the execs that they install in the firms they have stakes in) are looking for. So we pivoted.

Without going into too much detail, we are now exclusively focused on getting acquired by a big tech firm. Meetings with low-level product managers at a few of the world’s largest companies dictate every decision about which projects we pursue. We’re no longer building a company. We’re not even building a product. We’re building a feature that we hope will end up getting included in an app owned by a mega-corporation.

When I talk to my friends and peers at other tech startups, they tell me that it’s pretty much the same story at their companies. Everyone is building to the specifications set by Google or Amazon or Apple. This “competitive” industry, supposedly a shining example of the power of the free market, is really just a massive risk-free R&D department for the faang companies.40

The purposelessness of many professional careers in the capital accumulation economy starkly contrasts with the growing number of unaddressed needs in the public sector. The legions of finance drones making utterly pointless discounted cash flow models could be far better employed designing a serious industrial policy. The engineers currently laboring over algorithms to make social media more addictive should be funded to focus on more productive technological advances. All the effort now devoted to coming up with new pricing strategies for old drugs could be directed at real medical problems, like increasing resistance to antibiotics. The vast resources invested in unprofitable ride-hailing apps and real estate arbitrage could have been used to solve America’s ever-increasing public infrastructure and housing challenges.

In the early 1980s, opening up financial markets and other neoliberal reforms created many opportunities—which were both financially and personally rewarding—for professional elites. The New Deal institutions and “Nifty Fifty” corporations had by that time decayed into dull, IBM-ified bureaucracies. But Wall Street banks and investment firms were exciting places to work, populated by original and fascinating characters. The corporate world was in the midst of needed reorganization; new business models were being created; and Silicon Valley was just getting started.

Today, however, most of these workplaces are thoroughly routinized. Slogans about “changing the world” have long since morphed into PowerPoint slides on “widening the moat.” Elites climb 99 percent of the way up an ever-greasier pole only to spend most of their time focusing on cutting costs and increasing share buybacks—or marketing taxi services, vaping products, and food delivery as “technology.”

Government bureaucracies, to be sure, are as sclerotic and frustrating as ever. But the opportunity to restructure and revitalize the state—the only way to address the most important issues of the present—appears far more exhilarating to growing numbers of talented elites than any other alternative.

Adding insult to injury amidst—or, perhaps more accurately, behind—all of this is the absolute degeneracy of the American billionaire class. As if the present political and economic dysfunction were not enough to prove their corruption, our exalted plutocrats seem intent on publicly displaying their vacuousness.

Many of these people presumably possess some narrow technical ability, though if so, it is less and less evident. But they conspicuously lack any self-awareness, much less insight into issues of broader human concern, as will be obvious to anyone who bothers to read Ray Dalio’s autobiography. Likewise, one could watch every episode of David Rubenstein’s talk show vanity project, “Peer-to-Peer Conversations,” only to come away with the impression that Rubenstein has never asked an interesting question in his life. In fairness, however, he is not half as self-deluded as Tom Steyer, Michael Bloomberg, or Howard Schultz. The case of Donald Trump speaks for itself.

Conservative donor gatherings are somehow even more pathetic. Most of the attendees are there only because they are not smart enough to recognize that the Democratic Party offers a far more effective reputation laundering service. The rest are probably too senile to know where they are at all. There is often a special irony to these events: an uninspiring ideologue is usually on hand to repeat a decades-old speech decrying Communism—recounting the horrors experienced in countries ruled by a self-dealing, incompetent nomenklatura and marked by a decaying industrial base, crumbling infrastructure, poor education system, a demoralized populace, low confidence in public institutions, falling life expectancy, repeated foreign policy failures, a vast and arbitrary carceral system, constant surveillance, and even massive power outages in major cities.42 Imagine that.

The bold thinkers of Silicon Valley are at least as delusional. Mark Zuckerberg must be the only person in the world who still pretends to believe his self-serving banalities about “connecting people” through social media. Jeff Bezos publicly muses about the difficulty of finding a useful way to deploy his “financial lottery winnings,”43 while Amazon stations ambulances outside its warehouses to treat employees who collapse from exhaustion.44

At least Amazon and Facebook can claim to be successful companies, however. WeWork’s Adam Neumann, who recently received a $1.7 billion exit package, is leaving his firm in complete chaos. Shelved IPO filings describe Neumann as “a unique leader who has proven he can simultaneously wear the hats of visionary, operator and innovator, while thriving as a community and culture creator.”45 But the only entrepreneurial instinct he ever displayed was in ripping off his own company in related-party transactions.46 Neumann cannot even pretend to have pioneered a new business model; several other companies have been doing the same thing more successfully for years. He simply happened to be one of the cult-leader personas chosen by Softbank to enjoy the benefits of recent Bank of Japan monetary policies.47

In this case, Softbank should have taken a lesson from Google, which hired Eric Schmidt (after his dismal tenure at Novell) to serve as the buttoned-down figurehead for its IPO. Many industry observers believe Schmidt contributed virtually nothing to the company, but he became a billionaire because of his superior grasp of business etiquette: “Google policy is to get right up to the creepy line and not cross it,” he once said.48 Jeffrey Epstein, erstwhile dinner companion of Schmidt, Bill Gates, and seemingly every other member of this class,49 had a slightly different policy.

What is remarkable about today’s oligarchy is not its ruthlessness but its pettiness and purposelessness. An all-consuming megalomania might at least produce some great art as a side-effect. But this collection of mediocrities cannot even do that. Their political activities—whether pushing for a slightly lower tax rate or throwing money at a self-serving brand of faux progressivism—are too small-minded to be anything other than embarrassing. This class has no idea what to do with its wealth, much less the power that results from it. It can only withdraw and extract, socially and economically, while the political justifications for its existence melt away.

Ultimately, the question that will determine the future of American politics is whether the rest of the elite will consent to their continued proletarianization only to further enrich this pathetic oligarchy. If they do, future historians of American collapse will find something truly exceptional: capitalism without competence and feudalism without nobility.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume III, Number 4 (Winter 2019): 153–72. Notes

1 See also this summary of the work of Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman: Dylan Matthews, “You’re Not Imagining It: The Rich Really Are Hoarding Economic Growth,” Vox, August 8, 2017.

2 See, for example: Drew Desilver, “For Most U.S. Workers, Real Wages Have Barely Budged in Decades,” Pew Research Center, August 7, 2018.

3 Matthew Stewart, “The 9.9 Percent Is the New American Aristocracy,” Atlantic (June 2018).

4 “Ben Sasse: By the Book,” New York Times, November 21, 2018.

5 Chad Stone, et al., “A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 21, 2019.

6 See, for example: Noam Scheiber, “The Last Days of Big Law,” New Republic, July 21, 2013.

7 Bernard A. Burk and David McGowan, “Big but Brittle: Economic Perspectives on the Future of the Law Firm in the New Economy,” Columbia Business Law Review 1, no. 1 (2011), 1–117; Bernard A. Burk, “What’s New about the New Normal: The Evolving Market for New Lawyers in the 21st Century,” Florida State University Law Review 41, no. 3 (2014), 541–608.

8 Sara Randazzo, “Starting Law Firm Associate Salaries Hit $190,000,” Wall Street Journal, June 12, 2018.

9 Dan Packel, “Law Firms See Warning Signs of Slower Growth in 2019,” American Lawyer, May 14, 2019.

10 Yalman Onaran, “Wall Street’s Pay Slump since the Crisis Is Led by Goldman Sachs,” Bloomberg, September 16, 2019.

11 Onaran.

12 Michael P. Regan, “The Incredible Shrinking Hedge-Fund Fee,” Bloomberg, October 27, 2015.

13 Daniel Rasmussen, “Private Equity: Overvalued and Overrated?,” American Affairs 2, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 3–16.

14 Hubert Horan, “Uber’s Path of Destruction,” American Affairs 3, no. 2 (Summer 2019): 108–33.

15 Dan Lyons, Disrupted: My Misadventure in the Start-Up Bubble (New York: Hachette Books, 2016).

16 Moira Weigel, “Coders of the World Unite: Can Silicon Valley Workers Curb the Power of Big Tech,” Guardian, October 31, 2017.

17 Macy Bayern, “10 Tech Companies Where Employees Most Fear Being Laid Off,” TechRepublic, February 13, 2019.

18 Ryan Nunn and Jay Shambaugh, “San Francisco: Where a Six-Figure Salary Is ‘Low Income,’” BBC News, July 10, 2018.

19 Nunn and Shambaugh.

20 “Household Income Percentile Calculator for the United States,” DQYDJ, accessed October 2, 2019.

21 “Tuition Growth Has Vastly Outpaced Income Gains,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, accessed October 2, 2019.

22 Jennifer Medina, Katie Benner, and Kate Taylor, “Actresses, Business Leaders and Other Wealthy Parents Charged in U.S. College Entry Fraud,” New York Times, March 12, 2019.

23 Lawrence Mishel, Elise Gould, and Josh Bivens, “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts,” Economic Policy Institute, January 6, 2015.

24 Derek Thompson, “The Best Economic News No One Wants to Talk About,” Atlantic, October 5, 2019.

25 Alessandra Malito, “More Recent Graduates Are Living at Home than Ever Before,” MarketWatch, May 12, 2018.

26 Zaid Jilani and Ryan Grim, “Data Suggest that Gentrifying Neighborhoods Powered Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Victory,” Intercept, July 1, 2018.

27 Avi Asher-Schapiro, “Move Fast and Build Solidarity,” Nation, March 6, 2019.

28 “Warren Continues to Climb While Biden Slips Quinnipiac University National Poll Finds; Democratic Primary is Neck and Neck,” Quinnipiac University Poll, September 25, 2019.

29 Matthew Yglesias, “The Great Awokening,” Vox, April 1, 2019.

30 Barbara Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (New York: HarperPerennial, 1989), 155.

31 Nancy Fraser, “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond,” American Affairs 1, no. 4 (Winter 2017): 46–64.

32 Jeff Stein, “Bernie Sanders’s Base Isn’t the Working Class. It’s Young People,” Vox, May 19, 2016.

33 Sanders himself has basically admitted this difficulty, see: Tom McCarthy, “Bernie Sanders Explains His Primary Losses: ‘Poor People Don’t Vote,’” Guardian, April 24, 2016.

34 Brian Schwartz, “Wall Street Democratic Donors Warn the Party: We’ll Sit Out, or Back Trump, If You Nominate Elizabeth Warren,” CNBC, September 26, 2019. See also: Donald Shaw, “Hedge-Fund Billionaires Were Democrats’ Main Bankrollers in 2018,” American Prospect, May 16, 2019.

35 A refusal to acknowledge class interest is in some ways inherent to professional‑class identity, in part because this identity is necessarily based on disinterested expertise.

36 James Burnham was perhaps the only significant conservative thinker to recognize the importance and permanence of this class in his early work The Managerial Revolution: What Is Happening in the World (New York: John Day Company, 1941).

37 The Federalist Society is a possible exception in terms of personnel quality, precisely because political appointments still offer career advancement in law.

38 David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018).

39 Matt Stoller, “‘Very Few White-Collar Workers at P&G Really Do Anything . . . ,’” Big by Matt Stoller (blog), October 4, 2019.

40 Stoller.

41 Burk and McGowan, 26.

42 Thomas Fuller, “500,000 in California Are Without Electricity in Planned Shutdown,” New York Times, October 9, 2019.

43 Annie Lowrey, “Jeff Bezos’s $150 Billion Fortune Is a Policy Failure,” Atlantic, August 1, 2018.

44 Spencer Soper, “Inside Amazon’s Warehouse,” Morning Call, September 18, 2011.

45 Taylor Telford, “Adam Neumann’s Chaotic Energy Built WeWork. Now It Might Cost Him His Job as CEO,” Washington Post, September 23, 2019.

46 Derek Thompson, “WeWork’s Adam Neumann Is the Most Talented Grifter of Our Time,” Atlantic, October 25, 2019.

47 Emi Urabe, “Son Reshaping Softbank Seen in $20 Billion Loan,” Japan Times, August 1, 2013.

48 Jillian D’Onfro, “The 15 Wildest Things Google Chairman Eric Schmidt Has Ever Said,” Business Insider, November 2, 2013.

49 “Third Culture Schmoozing,” Wired, March 26, 2004.

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Monday, December 9, 2019

Former Ukraine Prosecutor Shokin: Joe Biden “Outraged We Seized Burisma Assets”, Could No Longer Pay His Son...

from the Conservative Treehouse

Rudy Giuliani traveled to Ukraine with OAN investigative journalist Chanel Rion. The U.S. media are going absolutely bananas after finding out Giuliani is now gathering even more information about Joe and Hunter Biden’s corrupt endeavors within Ukraine.

In this interview former Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin spoke to OAN about Joe Biden’s direct role in getting his office to stop investigating his son Hunter. The problem for Joe Biden was when Shokin seized all of Burisma’s assets the Ukranian gas company could no longer pay his son Hunter Biden. So the vice president demanded Shokin be removed.

When you combine this interview with the damning public statements delivered by the Ukraine prosecutor that replaced Shokin, Yuriy Lutsenko, things really get troublesome for Joe Biden, the Obama administration and Adam Schiff.

Prosecutor Yuriy Lutsenko stated that after he replaced Shokin he was visited by U.S. State Dept. official George Kent and Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch; they provided a list of corruption cases the Ukraine government was not permitted to follow.

Prosecutor Lutsenko dropping specific corruption cases was critical because that allowed/enabled a process of laundering money back to U.S. officials.

The potential for this background story to become part of a larger impeachment discovery is what has the U.S. media going bananas against Rudy Giuliani.

Senator Lindsey Graham is directly connected to the group of U.S. politicians who were participating in the influence network within Ukraine. One of the downstream consequences of Rudy Giuliani investigating the Ukraine corruption and money laundering operation to U.S. officials is that it ends up catching Senator Graham.

Hence, earlier today Senator Graham said he would not permit Senate impeachment testimony that touched on this corrupt Ukraine aspect.

In essence Senator Graham is fearful that too much inquiry into what took place with Ukraine from 2014 through 2016 will expose his own participation and effort along with former Ambassador Marie Yovanovich.

Graham is attempting to end the impeachment effort quickly because the underlying discoveries have the potential to expose the network of congressional influence agents, John McCain and Graham himself included, during any witness testimony.

Senators from both parties participated in the influence process, and part of their influence priority was exploiting the financial opportunities within Ukraine while simultaneously protecting fellow participant Joe Biden and his family.

If anyone gets too close to revealing the process, writ large, they become a target of the entire apparatus. President Trump was considered an existential threat to this entire process. Hence our current political status with the ongoing coup. The Giuliani letter:

It will be interesting to see how this plays out, because in reality many U.S. Senators (both parties) are participating in the process for receiving taxpayer money and contributions from foreign governments.

Those same senators are jurists on a pending impeachment trial of President Trump who is attempting to stop the corrupt financial processes they have been benefiting from.

The conflicts are very swampy….

FUBAR.

Sunday, December 8, 2019

Behind the Pay to Play Impeachment Hoax

In a fantastic display of true investigative journalism, One America News journalist Chanel Rion tracked down Ukrainian witnesses as part of an exclusive OAN investigative series. The evidence being discovered dismantles the baseless Adam Schiff impeachment hoax and highlights many corrupt motives for U.S. politicians.

Ms. Rion spoke with Ukrainian former Prosecutor General Yuriy Lutsenko who outlines how former Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch perjured herself before Congress.

What is outlined in this interview is a problem for all DC politicians across both parties. The obviously corrupt influence efforts by U.S. Ambassador Yovanovitch as outlined by Lutsenko were not done independently.

Senators from both parties participated in the influence process and part of those influence priorities was exploiting the financial opportunities within Ukraine while simultaneously protecting Joe Biden and his family. This is where Senator John McCain and Senator Lindsey Graham were working with Marie Yovanovitch.

Imagine what would happen if all of the background information was to reach the general public? Thus the motive for Lindsey Graham currently working to bury it.

You might remember George Kent and Bill Taylor testified together.

It was evident months ago that U.S. chargé d’affaires to Ukraine, Bill Taylor, was one of the current participants in the coup effort against President Trump. It was Taylor who engaged in carefully planned text messages with EU Ambassador Gordon Sondland to set-up a narrative helpful to Adam Schiff’s political coup effort.

Bill Taylor was formerly U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine (’06-’09) and later helped the Obama administration to design the laundry operation providing taxpayer financing to Ukraine in exchange for back-channel payments to U.S. politicians and their families.

In November Rudy Giuliani released a letter he sent to Senator Lindsey Graham outlining how Bill Taylor blocked VISA’s for Ukrainian ‘whistle-blowers’ who are willing to testify to the corrupt financial scheme.

Unfortunately, as we are now witnessing, Senator Lindsey Graham, along with dozens of U.S. Senators currently serving, may very well have been recipients for money through the aforementioned laundry process. The VISA’s are unlikely to get approval for congressional testimony, or Senate impeachment trial witness testimony.

U.S. senators write foreign aid policy, rules and regulations thereby creating the financing mechanisms to transmit U.S. funds. Those same senators then received a portion of the laundered funds back through their various “institutes” and business connections to the foreign government offices; in this example Ukraine. [ex. Burisma to Biden]

The U.S. State Dept. serves as a distribution network for the authorization of the money laundering by granting conflict waivers, approvals for financing (think Clinton Global Initiative), and permission slips for the payment of foreign money. The officials within the State Dept. take a cut of the overall payments through a system of “indulgence fees”, junkets, gifts and expense payments to those with political oversight.

If anyone gets too close to revealing the process, writ large, they become a target of the entire apparatus. President Trump was considered an existential threat to this entire process. Hence our current political status with the ongoing coup.

Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch, Senator Lindsey Graham and Senator John McCain meeting with corrupt Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko in December 2016.

It will be interesting to see how this plays out, because, well, in reality all of the U.S. Senators (both parties) are participating in the process for receiving taxpayer money and contributions from foreign governments.

A “Codel” is a congressional delegation that takes trips to work out the payments terms/conditions of any changes in graft financing. This is why Senators spend $20 million on a campaign to earn a job paying $350k/year. The “institutes” is where the real foreign money comes in; billions paid by governments like China, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Ukraine, etc. etc. There are trillions at stake.

[SIDEBAR: Majority Leader Mitch McConnell holds the power over these members (and the members of the Senate Intel Committee), because McConnell decides who sits on what committee. As soon as a Senator starts taking the bribes lobbying funds, McConnell then has full control over that Senator. This is how the system works.]

The McCain Institute is one of the obvious examples of the financing network. And that is the primary reason why Cindy McCain is such an outspoken critic of President Trump. In essence President Trump is standing between her and her next diamond necklace; a dangerous place to be.

So when we think about a Senate Impeachment Trial; and we consider which senators will vote to impeach President Trump, it’s not just a matter of Democrats -vs- Republican. We need to look at the game of leverage, and the stand-off between those bribed Senators who would prefer President Trump did not interfere in their process.

McConnell has been advising President Trump which Senators are most likely to need their sensibilities eased. As an example President Trump met with Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski in November. Senator Murkowski rakes in millions from the multinational Oil and Gas industry; and she ain’t about to allow horrible Trump to lessen her bank account any more than Cindy McCain will give up her frequent shopper discounts at Tiffanys.

Senator Lindsey Graham announcing today that he will not request or facilitate any impeachment testimony that touches on the DC laundry system for personal financial benefit (ie. Ukraine example), is specifically motivated by the need for all DC politicians to keep prying eyes away from the swamps’ financial endeavors. WATCH:

This open-secret system of “Affluence and Influence” is how the intelligence apparatus gains such power. All of the DC participants are essentially beholden to the various U.S. intelligence services who are well aware of their endeavors.

There’s a ton of exposure here (blackmail/leverage) which allows the unelected officials within the CIA, FBI and DOJ to hold power over the DC politicians. Hold this type of leverage long enough and the Intelligence Community then absorbs that power to enhance their self-belief of being more important than the system.

Perhaps this corrupt sense of grandiosity is what we are seeing play out in how the intelligence apparatus views President Donald J Trump as a risk to their importance.

FUBAR !

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Friday, November 22, 2019

On the Constant Drip, Drop, Drip of Intelligence Leaks onto/ into the Daily Newspapers

And with the help of big names in media they’re turning journalism into an intelligence operation

There are two sets of laws in the United States today. One is inscribed in law books and applies to the majority of Americans. The other is a canon of privileges enjoyed by an establishment under the umbrella of an intelligence bureaucracy that has arrogated to itself the rights and protections of what was once a free press.

The media is now openly entwined with the national security establishment in a manner that would have been unimaginable before the advent of the age of the dossier—the literary forgery the FBI used as evidence to spy on the Trump team. In coordinating to perpetrate the Russiagate hoax on the American public, the media and intelligence officials have forged a relationship in which the two partners look out for the other’s professional and political interests. Not least of all, they target shared adversaries and protect mutual friends.

Recently WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was indicted on 17 counts of violating the espionage act for obtaining military and diplomatic secrets from U.S. Army intelligence officer Chelsea Manning and publishing them in 2010. First Amendment lawyers and free speech activists worry that the indictments are likely to have a “chilling” effect on the practice of journalism. Others, however, argue that the First Amendment doesn’t apply to the WikiLeaks founder.

“Julian Assange is no journalist,” Assistant Attorney General for National Security John Demers said in a press briefing last week.

The Department of Justice’s position found support, of all places, in the media. “Julian Assange himself is not a journalist,” said CNN national security and legal analyst Asha Rangappa. “He was not engaged in bona fide newsgathering or publication and put national security at risk intentionally,” Rangappa told NPR.

Who’s Asha Rangappa, you ask, and how did she become an expert on journalism?

According to a profile in Elle magazine, she worked three years in the FBI (Robert Mueller was director) as a counterintelligence official in the New York field office before returning to her alma mater, Yale Law School, as its admissions director. In that post she became famous for destroying admissions records to prevent students from legally accessing them. With the advent of the Russiagate hoax, Rangappa has become one of the best-known faces of a new, hybrid industry in which former national security bureaucrats are rebranded as “journalists.”

Here are the people that Americans get their national security news from these days:Before becoming a national security analyst for CNN, former director of national intelligence, James Clapper, had previously been a news item himself after lying to Congress in 2013 when he testified that the NSA wasn’t collecting data on Americans. He later provided inconsistent testimony to Congress in 2017—saying first that he had not spoken with the press about the Steele dossier while he was DNI, then that he told future CNN colleague Jake Tapper about it. According to Tapper, that never happened. What’s clear is that Clapper should not be offered up as any kind of expert by any legitimate outlet.Other members of CNN’s shadow intelligence organization include Josh Campbell, one-time special assistant to ex-FBI Director James Comey, and CIA official Philip Mudd. What qualifies them as journalists, as opposed to Assange? They worked in the intelligence community.

CNN rival NBC/MSNBC features an even more formidable roster of spooks. At the top is John Brennan, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency. During his time at the helm of the CIA, the agency spied on Congress, lied about it and finally got outed by an internal report forcing Brennan to issue apologies to the senators who had been targets of the intelligence operation. “The C.I.A. unconstitutionally spied on Congress by hacking into the Senate Intelligence Committee computers,” Colorado Democratic Sen. Mark Udall wrote at the time. In a statement calling on Brennan to resign, Udall wrote: “This grave misconduct not only is illegal but it violates the U.S. Constitution’s requirement of separation of powers” and called the episode evidence of “a tremendous failure of leadership.”

Another NBC contributor is former CIA analyst Ned Price, who as Obama national security staff spokesman misled the U.S. press and public regarding Obama administration policy.

NBC reporter Ken Dilanian said of the WikiLeaks founder: “Many believe that if [Assange] ever was a journalist, those days ended a long time ago.” Others have said the same of Dilanian, based on a 2014 report showing that the NBC journalist was sending his articles to CIA headquarters for fact-checking.

NBC was named in a defamation lawsuit last week filed by the lawyer for a British academic, Svetlana Lokhova, a Moscow-born historian who was dragged into a US intelligence operation to frame Trump’s former national security adviser, Michael Flynn, as a Kremlin asset. Lokhova was accused without any evidence whatsoever of being a Russian spy by several U.S. and U.K. press outfits.

MSNBC’s Malcolm Nance—whose Twitter feed identifies him as “US Intelligence +36 yrs. Expert Terrorist Strategy, Tactics, Ideology. Torture, Russian Cyber!”—was one notable player in the journalist-spook nexus pumping up the story that Lokhova was a spy who ensnared Flynn. In early 2017 Nance tweeted: “Flynn poss caught in FSB honeypot w/female Russian Intel asset.”

Fellow MSNBC contributor Naveed Jamali— author of How to Catch a Russian Spy and a self-described “Double agent” and “Intel Officer”—joined in tweeting: “Here’s the other thing to understand about espionage: once you’ve crossed the line once, the second time is easier. While at DIA Flynn had contact with Svetlana Lokhova who allegedly has Russian intel ties.”

Lokhova is seeking $25 million from NBC, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Dow Jones & Co., owner of the Wall Street Journal, and U.S. government informant Stefan Halper. The British historian alleges that Halper was the source for the press’ multipronged smear campaign against her, a private citizen.

Unlike the New Journalists at CNN and MSNBC/NBC, Julian Assange meets the old-fashioned definition of a journalist, meaning a person who is willing to take personal risks to publish information that powerful people and institutions routinely lie to the public about in order to advance their political and personal agendas.

And yet it’s true that the leaks Assange published in 2010 may have endangered U.S. troops in Afghanistan and Iraq. Further, by failing to redact those documents—as WikiLeaks colleagues reportedly urged—Assange may have put a price on the heads of informants who came forth to help the United States.

Former CIA Director Robert Gates said in 2010 that Assange was morally culpable. “And that’s where I think the verdict is ‘guilty’ on WikiLeaks. They have put this out without any regard whatsoever for the consequences.”

Gates was less certain that Assange damaged U.S. interests. The longtime public servant acknowledged that the publication of the 2010 leaks was embarrassing and awkward. “Consequences for U.S. foreign policy?” said Gates. “I think fairly modest.”

Commentators claim that the indictments have nothing to do with Assange’s publishing stolen Democratic National Committee emails in the months before the 2016 election that might have damaged Hillary Clinton’s candidacy. That is not true. The purpose of the indictments, like the Russiagate hoax itself, is to send a message. The U.S. security establishment will use both legal and extraconstitutional methods to protect its privileges and prerogatives while waging a relentless campaign against anyone who dares to encroach on them.

The indictments against Assange further confirm the dossier-era degradation of the American public sphere, where spies are now in charge of shaping the news, with the goal of advancing their own institutional agendas, prosecuting political hits, and keeping themselves and their political patrons beyond the reach of the laws that apply to everyone else.

***

“No responsible actor, journalist or otherwise, would purposefully publish the names of individuals he or she knew to be confidential human sources in a war zone,” John Demers said during last week’s press briefing on the Assange indictments.

The head of DOJ’s national security division also thanked the media for their role in protecting American democracy. But how the Justice Department apparently understands its cozy bureaucratic partnership with New Journalists like Asha Rangappa and her colleagues is worth looking at.

In late March, Demers sat for an hour-long public interview with Washington Post reporter Ellen Nakashima to discuss the challenges facing DOJ and the National Security division—including China, Iran, and of course Russia.

Nakashima was part of the joint New York Times and Washington Post team that won a 2018 Pulitzer Prize “for deeply sourced, relentlessly reported coverage in the public interest that dramatically furthered the nation’s understanding of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and its connections to the Trump campaign, the President-elect’s transition team and his eventual administration.”

Many of the 20 stories cited by the Pulitzer committee appear to be sourced to leaks of classified information. Demers’ interlocutor in March had her byline on one of the Pulitzer-cited Post stories that, if the reporting is to be believed, was sourced to leaks of classified information drawn from an intercept of a foreign official.

A Feb. 9, 2017, Post story by Nakashima, Adam Entous, and Greg Miller reported on former Trump official Michael Flynn’s conversation with then-Russian ambassador to the United States Sergei Kislyak. The story related details from the conversation, and is sourced to “officials who had access to reports from U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies that routinely monitor the communications of Russian diplomats.”

It’s useful comparing the nature of the leaks Assange published and those made public by the Post. Of the more than 250,000 diplomatic cables that WikiLeaks published, half were unclassified. The rest were mostly classified “Confidential,” with 11,000 classified “Secret.” None are classified “Top Secret.” The reports regarding Afghanistan, Iraq, and Guantanamo Bay were classified no higher than “Secret.”

By contrast, intercepts of foreign officials, like the one regarding the Russian ambassador, are so sensitive that they are available only to a very few senior U.S. officials. The fact that the substance of one such intercept appears to have been leaked and discussed, according to the Post, by nine U.S. officials, should have sparked an immediate investigation.

The Justice Department did not respond to Tablet’s email asking whether any of the nine officials who discussed the Flynn leak are currently under investigation.

Another story with a Nakashima byline, dated July 21, 2017, reported on communications between Kislyak and Moscow regarding the ex-envoy’s conversations with former Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The conversations, write Nakashima and her Post colleagues, “were intercepted by U.S. spy agencies.” This story was also sourced to U.S. officials.

DOJ did not respond to Tablet’s email asking whether the U.S. officials who discussed the Sessions leak are under currently under investigation.

DOJ also did not respond when asked if Nakashima and the other Pulitzer-Prize-winning Post reporters who published stories sourced to classified information are under investigation.

Nakashima did not respond to an email from Tablet requesting comment for publication. Washington Post Executive Editor Martin Baron did not respond by press time to emails requesting comment for publication.

So should Nakashima and her colleagues be held to the same legal standards as Julian Assange? Of course not. Assange was in trouble, Rangappa reasoned, because he “was not a passive recipient of classified information the way that a journalist who is receiving … an anonymous leak might be, that he was actively participating in the solicitation encouragement of – in the process of getting this information illegally.”

Yet the Post and the Times can hardly be considered “passive recipients” of “an anonymous leak.” The leaks were provided not by whistleblowers outing the wrongdoings of government officials—which was Assange’s territory. Rather, the Post and Times gave a platform to U.S. officials who abused surveillance programs and other government resources in order to prosecute a political campaign against the sitting president and his advisers. The Pulitzer citation itself provides a timeline showing that the stories are evidence of a campaign of leaks lasting more than half a year.

Yes, Assange’s leaks may have endangered American troops and certainly put foreign nationals at risk. Assange also endangered national security by exposing sources. And yet the Post and the Times were active participants in a political operation that abused surveillance programs designed to keep Americans safe from terrorism. Who endangered American national security more?

Many journalists now claim to be concerned about President Trump’s ordering Attorney General William Barr to declassify documents related to the FBI’s Russia investigation–a move that old fashioned truth seekers should surely welcome. The worry now, say media industry insiders, is that declassification may reveal sensitive government sources. However, there was little media concern that the campaign of Russiagate leaks targeting the Trump circle endangered U.S. citizens or foreign nationals.

Here, for instance, is an April 11, 2017, Ellen Nakashima story, again seemingly sourced to classified information, disclosing that the FBI had a surveillance warrant on Trump campaign adviser Carter Page on suspicion he was a Russian agent. The former U.S. Navy officer was subjected to a campaign of harassment, including death threats. British historian Svetlana Lokhova was also subjected to abuse and harassment.